If you look closely at the technologies and habits that define how we live and think now, echoes of the Renaissance ring louder than you might expect. The Renaissance isn’t just art in gilded frames or ancient books locked in libraries. It produced specific innovations—in visual perception, chemistry, mass communication, funding systems, and scientific study—that structured the world beneath our feet. In many ways, the era acts as a hidden architect behind day-to-day reality. Why do our eyes accept a painted image as a real window? Why can ideas travel continents in seconds? Why does a city’s burst of creativity reshape industries? These questions all have roots in the five innovations I want to guide you through.

Let’s start with linear perspective. Picture trying to draw a three-dimensional world onto a flat page. Before Brunelleschi formalized the rules, artists guessed, relying on intuition and awkward shortcuts. His insight—a simple set of geometric rules—opened new possibilities. Suddenly, people could create images with convincing depth, not only in paintings but also in blueprints, mapmaking, and engineering. More than a visual trick, linear perspective changed how architects planned buildings and how navigators thought about space. The same mathematical thinking behind Renaissance perspective shapes modern video game graphics, urban planning, and the GPS paths we take for granted. “The artist is an inventor of another world,” Leonardo da Vinci once said, and linear perspective is the grammar that makes these worlds believable.

How often do you stop to look—really look—at a patch of old oil paint, the way it catches and reflects light? The Renaissance’s perfection of oil painting wasn’t just about aesthetics. Artists like Jan van Eyck discovered ways to mix oil-based pigments with translucent glazes, layering and adjusting over weeks or months. This let artists achieve not only more realistic textures but also new subtleties in mood and meaning. The technical information these painters gathered—about drying, light, substances—fed directly into the emerging sciences of optics and chemistry. So, the glimmer on a saint’s forehead or the glint of a gold ring in a centuries-old portrait isn’t just a mark of artistic brilliance; it’s an early experiment in how matter interacts with light, paving the way for later advances in photography and forensics. I often ask myself: Would Hollywood’s mastery of light and CGI even be possible without those early oil painters perfecting their craft?

Let’s turn to a device that rarely gets its due for shaping the modern mind—the printing press. Before Gutenberg, producing a book was a marathon: months or even years of hand-copying. Gutenberg’s press, with movable metal type and durable oil-based ink, changed time itself. Suddenly, books could be mass-produced, making knowledge affordable and mobile. This radically democratized learning. Protestant reformers used pamphlets to ignite revolutions. Scientists like Copernicus and Galileo circulated controversial findings, fueling debates that built the scaffolding for the scientific method. Alphabetic literacy rates climbed, and for the first time, a cobbler in Mainz could debate a merchant in Florence about the latest astronomical theory.

“The printing press,” said Victor Hugo, “is an army of twenty-six lead soldiers that conquered the world.” Isn’t it remarkable how every social network and digital news feed today walks a path first paved by rows of metal type?

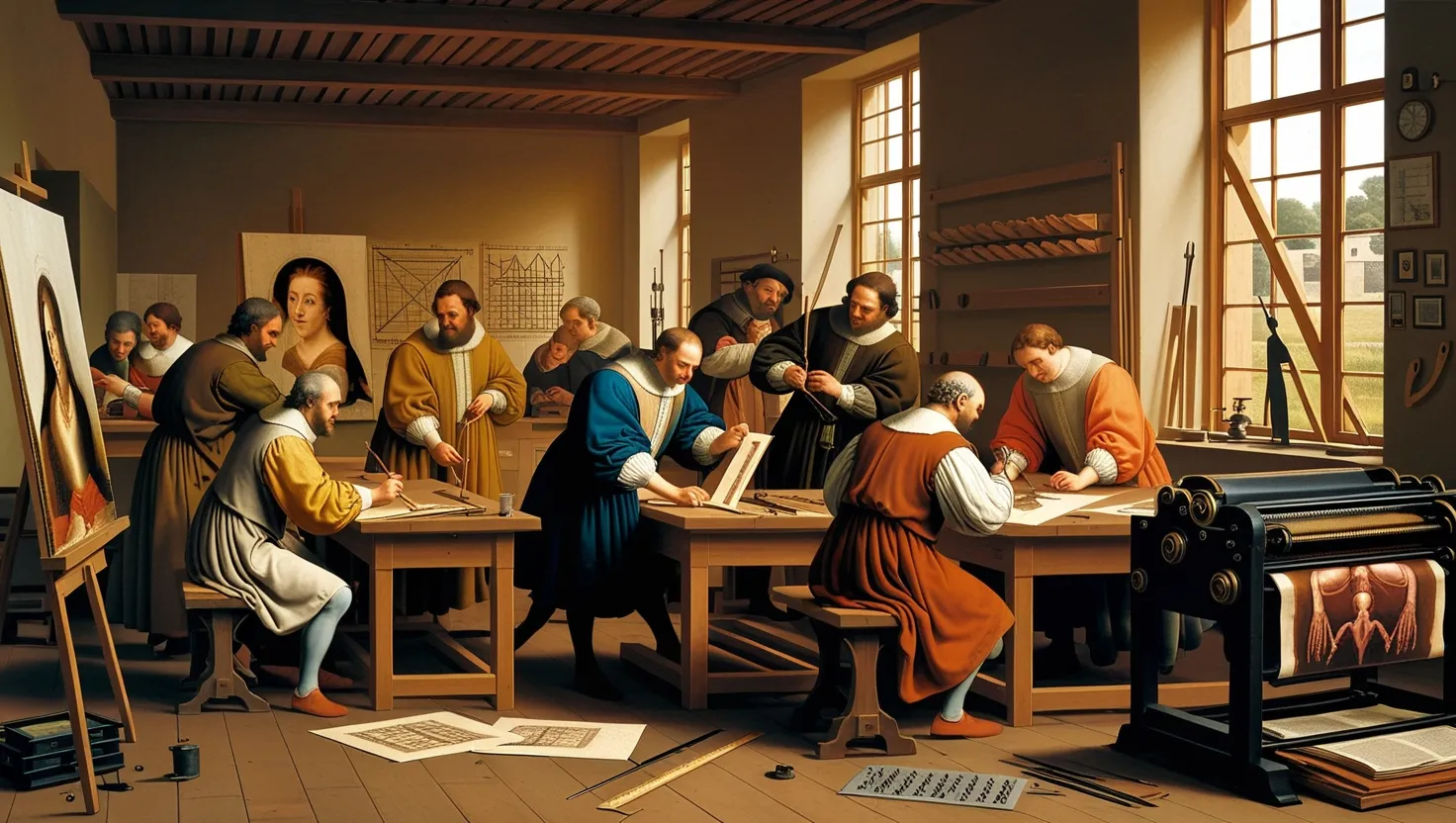

But mass production of ideas needed fuel—and for creative work, that meant patronage networks. When we picture Renaissance sponsorship, it’s tempting to focus on powerful families ordering grand portraits for their estates. In reality, systems of support were far more structured and strategic. The Medici didn’t just sponsor one painter—they helped build workshops, foster multidisciplinary groups, and fund experimental thinkers. Some of these sponsored projects included anatomical research, engineering stage mechanisms for theater, and even designing urban water supplies. These networks were, in a sense, the world’s first research and innovation hubs—long before Silicon Valley or government science grants. Today’s tech incubators and philanthropic foundations stand on their shoulders.

A favorite quote of mine from Lorenzo de’ Medici: “The power of the mind, once expanded to take in new knowledge, never returns to its original dimension.” Consider this: Would we have modern university labs, collaborative studios, or startup accelerators if Renaissance patronage hadn’t demonstrated their value?

This brings me to one of the era’s most surprising legacies: the marriage of art and anatomy. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci were obsessed with capturing the human figure at its most precise. To do that, they became pioneers of anatomical science, often working in dim, uncomfortable conditions, secretly dissecting bodies to map muscle, tendon, and bone. This search wasn’t just artistic—it directly challenged inherited medical dogma, shifting the practice of medicine from faith in old texts to direct observation and repeated study. Da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, for example, aren’t merely beautiful; they were vastly more accurate than most doctor’s manuals of the time. And their approach—test, observe, question—planted beans that would grow into modern biology, surgery, and medical illustration.

“Where the spirit does not work with the hand, there is no art,” Leonardo once claimed. And in this context, there’s a more literal meaning: the Renaissance spirit insisted that skilled hands and curious minds move together, whether painting a portrait or performing an autopsy.

Take a moment and ask yourself: How many of the basic principles behind the smartphone in your pocket, the MRI scanner at a local hospital, or the digital map guiding a road trip, can you trace back to these innovations? The pattern is everywhere. The Renaissance habit of cross-pollinating disciplines—artists learning anatomy, engineers studying optics, bankers fostering research—is hardly obsolete. In fact, the most striking changes of the 21st century echo them.

Most histories highlight the big names, the da Vincis and the Michelangelos, but it’s the system—the methods and attitudes—that ran deeper. Renaissance “workshops” operated as true teams, mixing apprentices, experts, and polymaths. They worked across boundaries, connecting metalwork with painting, or hydraulics with sculpture. That collaborative spirit, more than any single invention, shows up today in everything from open-source projects to interdisciplinary science teams. When multiple minds approach a problem from several directions, innovation flourishes.

What’s often overlooked is how Renaissance innovations began to shift social and economic power. With mass printing, access to information became less about noble birth and more about literacy. With oil paints and perspective, more people could participate in the conversation about beauty, reality, and truth. Anatomy and scientific inquiry brought more reliable treatment—and greater trust in evidence-based reasoning. The patronage model hinted at the value of concentrated groups of talent, inspiring city governments, companies, and philanthropists to invest in clusters of expertise.

If I could ask any Renaissance thinker one question, it would be: Did you imagine how far your innovations would ripple? Could you foresee our global networks, the billions of photographs, the life-saving surgeries, the way knowledge leaps borders almost instantly?

Sir Francis Bacon once declared, “Knowledge is power.” The Renaissance, by forging new ways to see, record, fund, and study the world, distributed that power—and the process is still unfolding.

So the next time you flip through a book, step inside a lifelike virtual world, or consult a detailed medical chart, remember: you are participating in Renaissance thinking. The threads spun centuries ago continue to bind and expand our reality. And if you ever doubt whether art and science belong together, recall that they grew up as twins, learning from and amplifying each other.

That’s the quiet legacy of the Renaissance’s hidden innovations—forever part of how we see, question, and build. Would the world have been transformed anyway? Perhaps. But not with the same poetry, precision, or persistent urge to connect across all boundaries.