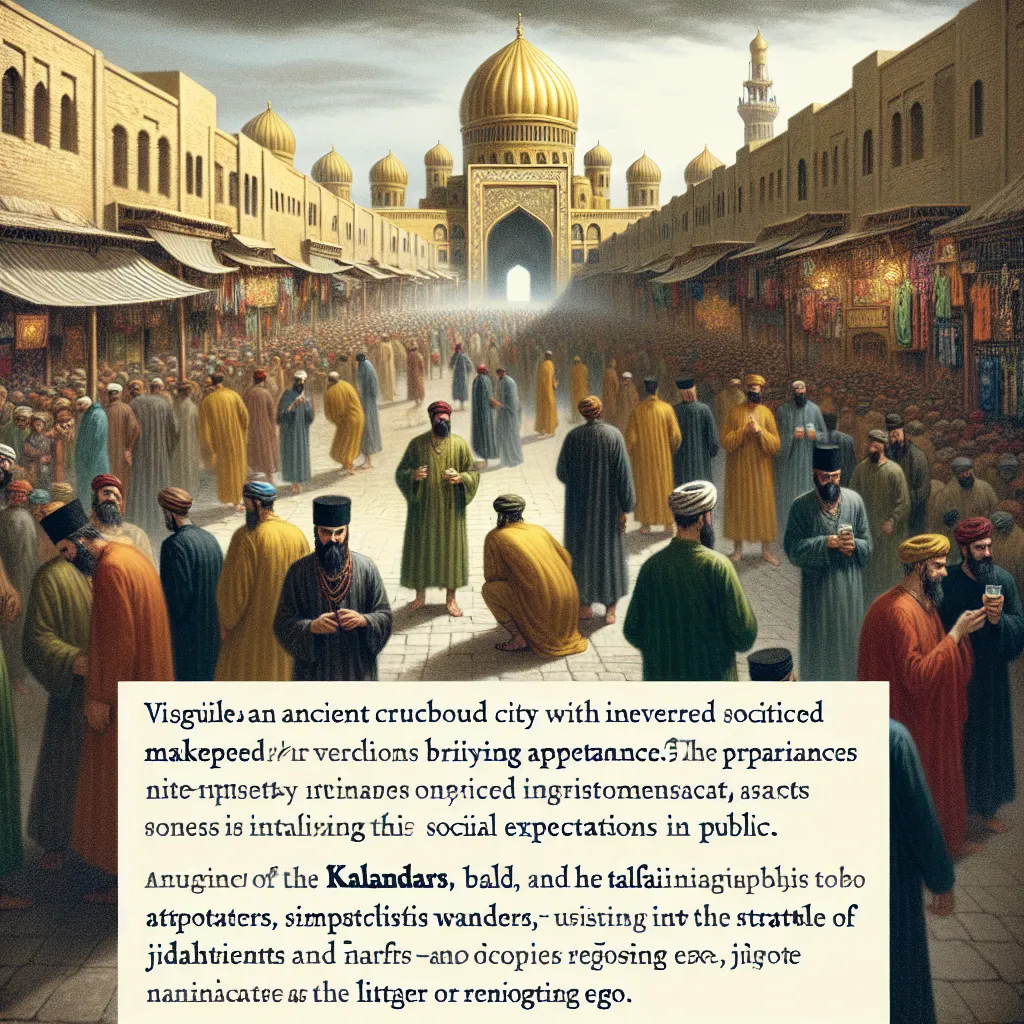

Imagine a bustling city like Herat, with its narrow streets and lively markets, suddenly buzzing with excitement because a revered mystic is about to arrive. Crowds gather, eager to catch a glimpse and follow this man rumored to have incredible spiritual powers. But when he publicly urinates in an improper way, the crowd scatters, and their admiration quickly turns to disbelief. This moment illustrates a fascinating aspect of Sufi mysticism and brings us into the world of the Kalandar.

Kalandars, like other antinomian groups in Islamic mysticism, are notorious for their controversial behavior. They often defy social and religious norms to achieve spiritual purity by rejecting their egos, or Nafs. This journey, called Jihad al-Nafs, is a personal struggle to surrender oneself entirely to God.

The story of the Kalandar is deeply intertwined with the broader history of Islamic mysticism. Historically, the city of Nishapur in the Khorasan region was a hotbed for a group called the Malamatiya. These mystics believed showing visible acts of piety was detrimental because it fed the ego they were striving to eliminate. They preferred to hide their piety and sometimes acted in ways that invited public blame rather than praise. The idea was that by being scorned, they could more effectively battle their inner egos.

As you delve into the history of the Kalandar, you find they pushed these ideas to more radical extremes. They originated in places like Damascus and Egypt but were predominantly Persian. Their lives were marked by extreme asceticism and a disdain for societal norms, often neglecting obligatory prayers and fasting, living as wandering ascetics with no possessions. They shaved off all their hair, including beards and eyebrows—a shocking act in a society where such practices were taboo.

Much like the Sufi poets who spoke of wine, taverns, and love for God through metaphorical language, Kalandars often took these themes quite literally. They used music, dance, and intoxicants like hashish as integral parts of their spiritual practice. These mystics believed in dying to both this world and the next, following the Prophet Muhammad’s saying of “die before you die.”

Their impact wasn’t just philosophical but practical as well. The Kalandar movement wasn’t confined to one place; it spread across the Islamic world, from the Arab-speaking regions to the Indian subcontinent, and even the Ottoman Empire. In Anatolia, the Bektashi order, initially influenced by Kalandar practices, became an essential part of the Janissary corps, the elite soldiers of the Ottoman Empire.

As time went on, some of these antinomian groups transitioned into more formal Sufi orders, like the Mevlevis who followed Rumi. However, not all retained their radical practices, evolving instead into more accepted and orthodox forms.

Today, the direct influence of Kalandars might not be as widespread, but their legacy lives on in poetry, music, and the ethos of certain Sufi orders. They add a colorful, often misunderstood chapter to the rich tapestry of Islamic mysticism, highlighting how varied and complex spiritual paths can be.

So, the next time you listen to a Qawwali performance by someone like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan singing about the mystical experiences of the Kalandars, you’ll know it’s more than just a song. It’s a glimpse into a brave, rebellious tradition that sought to find God by breaking every rule in the book.