Ancient Mesopotamia, often hailed as the cradle of civilization, thrived between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in what is now modern-day Iraq. It’s credited with many firsts, including the invention of writing and the formation of some of the earliest cities and empires. This culture significantly influenced subsequent civilizations and left an enduring legacy in various aspects of human development.

Mesopotamia boasted a rich and complex religious tradition, often misunderstood and sensationalized. Scholars and archaeologists, however, have provided us with a clearer picture of their faith. The religious practices and deities of ancient Mesopotamia not only shaped their own society but also laid the groundwork for some elements found in later Abrahamic religions.

Dating back thousands of years, Mesopotamian civilization evolved significantly. Different periods and regions within Mesopotamia shared certain religious characteristics, but practices and interpretations varied. The civilization emerged in regions identified as Sumer and Akkad, inhabited by the Sumerians with their non-Semitic language and the Akkadians who spoke the earliest known Semitic tongue.

Writing emerged within this cultural melting pot, initially dominated by the Sumerian language. Over time, Akkadian became the spoken language, while Sumerian remained in use for sacred and scholarly writings. This dual linguistic heritage is reflected in the names of many gods, which often had both Sumerian and Akkadian versions.

Throughout its millennia-long history, various political entities rose and fell in Mesopotamia. Early on, Sargon of Akkad established what some consider the first empire, followed by the Babylonian Empire under Hammurabi, and later the Assyrian Empire. These powerful states left an influential legacy, and while their political stability varied, they consistently contributed to a unified Mesopotamian civilization.

At the heart of Mesopotamian religion was polytheism—a belief in many gods who created and governed the universe. Deities were associated with natural phenomena and human concepts. For example, Shamash (Utu in Sumerian) was the sun god, and Ishtar (Inanna in Sumerian) was a goddess of love and war. Each city had a patron deity, with major temples serving as the focal points of worship.

The religious structure reflected societal hierarchies, with certain gods holding higher status. Notable deities included Anu, the highest god; Enlil, the god of air and king of gods; and Marduk, who became paramount in Babylonian times.

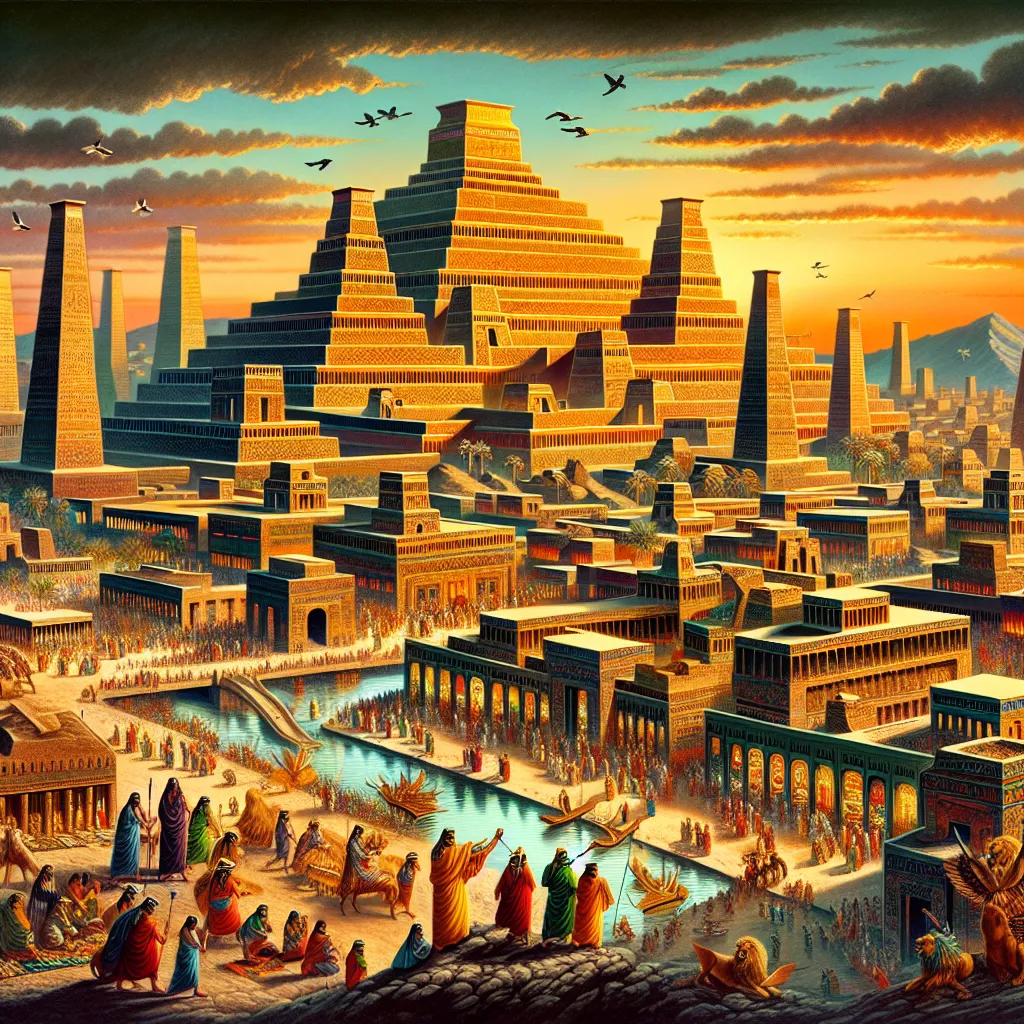

Religious practices revolved around making the gods comfortable. Temples, seen as divine dwellings, were staffed with priests who provided elaborate care, including daily meals and rituals. These sacred sites often featured ziggurats—massive towers with shrines at the top. The priests also performed sacrifices, sang hymns, and played music to honor the gods.

Religion intertwined with governance; kings legitimized their rule through divine connection. For instance, the Assyrian Empire’s chief deity, Ashur, played a vital role in royal legitimacy. This intertwining of religion and politics reinforced social order and maintained cosmic balance.

While centered in temples, Mesopotamian worship extended to everyday life. Common people practiced devotion through offerings and prayers, and festivals reenacted divine myths, engaging entire communities. Divination and astrology were also crucial, as they believed the gods communicated future events through signs.

Even in their decline, Mesopotamian religious practices influenced subsequent cultures and religions. Their legacy is evident in biblical stories, Greek philosophy, and the broader history of human spirituality.

Understanding ancient Mesopotamian religion offers invaluable insights into the origins of human civilization and the evolution of religious thought. The spiritual life of Mesopotamia is a testament to the enduring power of faith in shaping and explaining the human experience.