Many animals need sleep, even brainless jellyfish. They pulse less and respond more slowly to food and movement when they’re in a sleep-like state. But threats and demands don’t just vanish when it’s time to doze off. Birds and mammals often engage in asymmetrical sleep, where parts of their brains are asleep while others remain more active. This quirky sleep pattern even applies to humans.

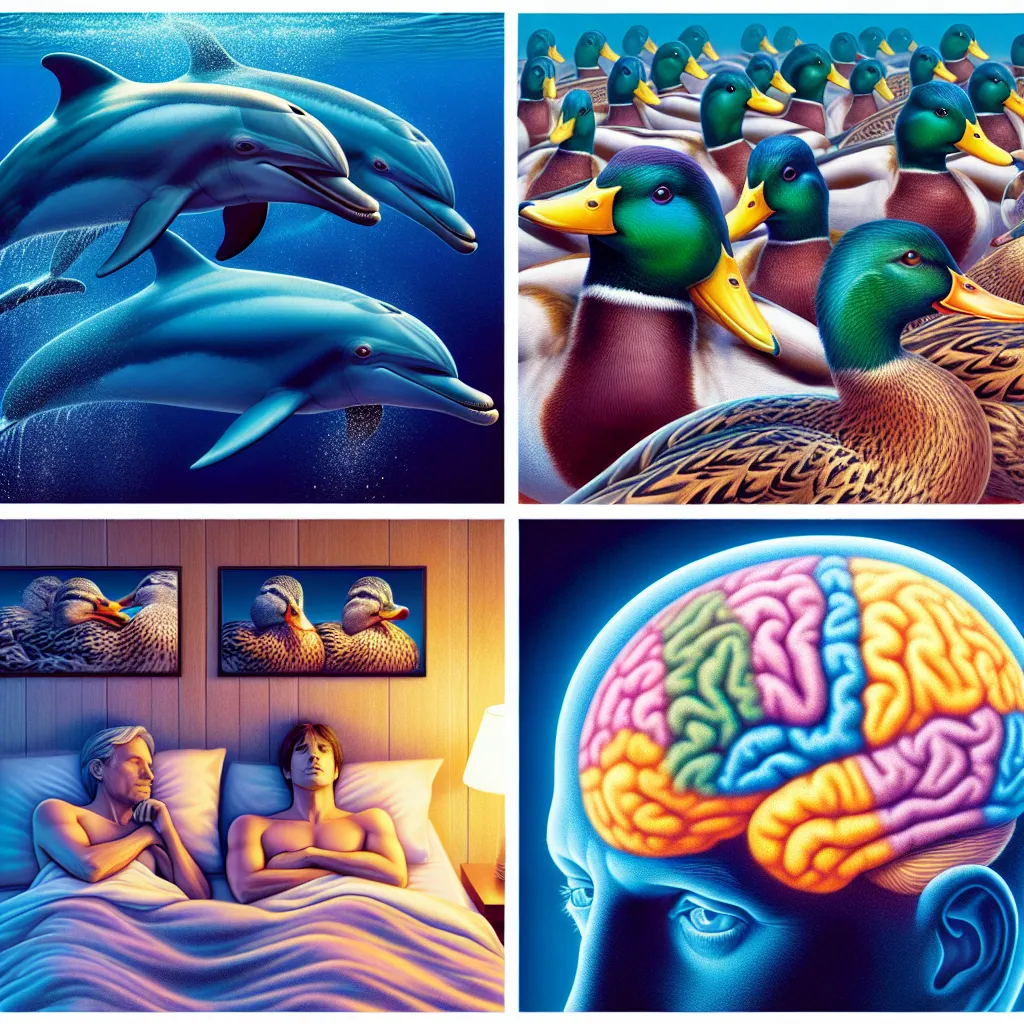

The brain is split into two hemispheres: the right and left. Typically, brain activity is similar across both sides during sleep. But during asymmetrical sleep, one hemisphere can be in deep sleep while the other stays in lighter sleep. In extreme cases, called “unihemispheric sleep,” one hemisphere can seem completely awake while the other is deeply asleep.

Take bottlenose dolphins, for instance. They consciously control their breathing and need to surface for air every few minutes to avoid drowning. To keep a newborn calf safe, they have to swim nonstop for weeks. Dolphins sleep unihemispherically, with one hemisphere at a time, allowing them to keep swimming and breathing while they snooze. Other marine mammals also rely on asymmetrical sleep. Fur seals, for instance, might migrate at sea for weeks, slipping into unihemispheric sleep. They float horizontally with their nostrils above the surface, one eye closed, and the other open to stay alert to threats from below.

Birds face similar pressures. Mallard ducks often sleep in groups with some at the peripheries. Those ducks engage in unihemispheric sleep, keeping their outward-facing eyes open. Some birds even sleep midair during long migrations. Frigatebirds, for example, undertake non-stop transoceanic flights of up to 10 days, sleeping with one or both hemispheres in short bursts. They ride air currents and sleep less than 8% of what they would on land, showing great tolerance for sleep deprivation.

It’s still unclear if asymmetrical sleep offers the same benefits as full-brain sleep or how these benefits vary across species. In one experiment, fur seals preferred full-brain sleep after being constantly stimulated, suggesting it was more restorative for them. On the other hand, dolphins can stay highly alert for at least five days by switching which hemisphere is awake, getting several hours of deep sleep in each hemisphere over 24 hours. This might be why unihemispheric sleep alone meets their needs.

So what about humans? Have you ever woken up groggy after your first night in a new place? Part of your brain might have spent the night only somewhat asleep. Scientists have long recognized that people sleep poorly on their first night in a lab. It’s customary to discard that night’s data. In 2016, scientists found this “first night effect” is a subtle form of asymmetrical sleep in humans. During the initial night, participants had deeper sleep in their right hemisphere and lighter sleep in their left. When exposed to sounds, the lighter sleeping left hemisphere showed greater activity bumps. Participants woke up and responded to sounds faster than when experiencing deep sleep in both hemispheres on subsequent nights.

This suggests humans use asymmetrical sleep for vigilance, especially in unfamiliar environments. So, even if your hotel room isn’t trying to eat you and you won’t die if you stop moving, your brain is still on high alert. Just in case.