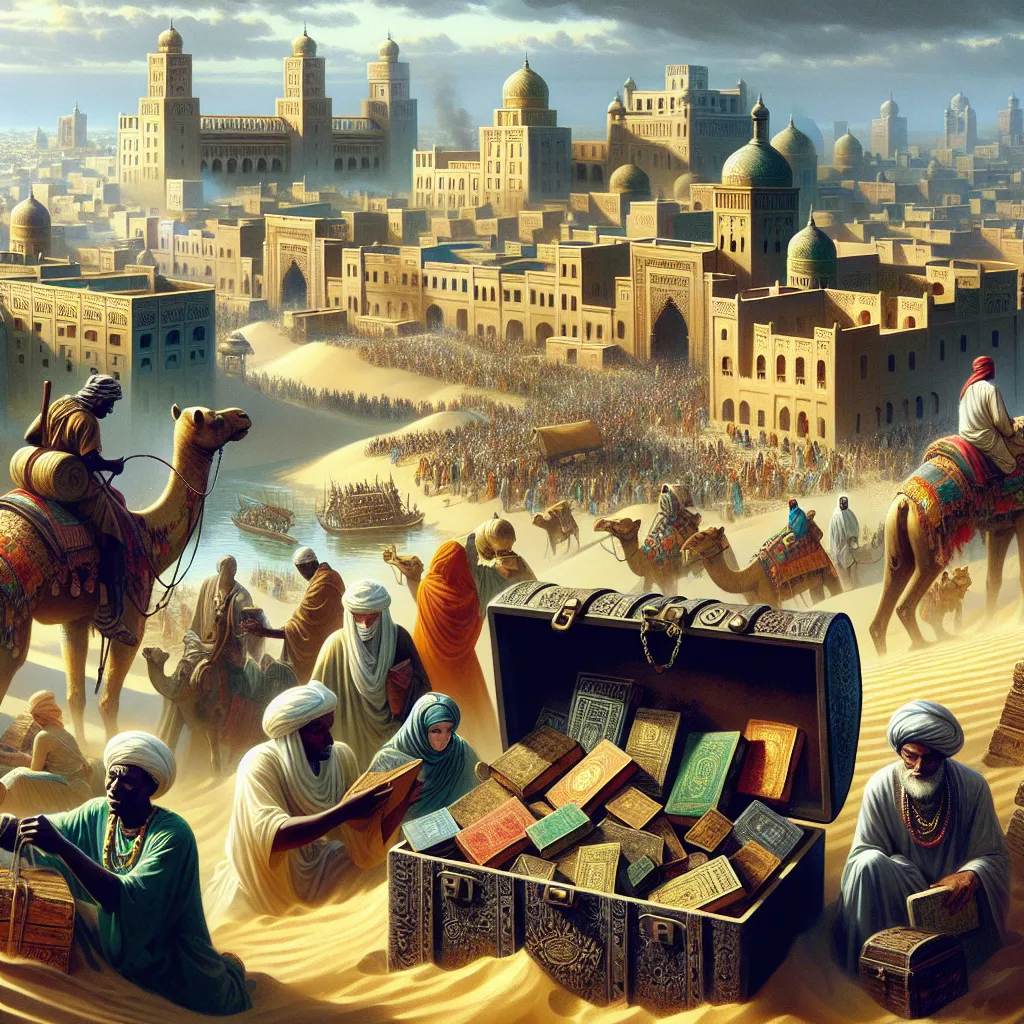

On the edge of the endless Sahara desert, the folks of Timbuktu took drastic measures to safeguard their heritage. They ventured into the wilderness, burying chests filled with ancient books in the sand, stashing them in caves, and sealing them in secret rooms. These books were treasures far more valuable than gold.

Timbuktu, founded around 1100 CE in present-day Mali, started as a humble trading post. Its strategic location, however, soon placed it at the crossroads of two crucial trade routes. Caravans transported salt across the Sahara, while traders brought gold from the African interior. By the late 1300s, these routes made Timbuktu a wealthy hub. The rulers of the Mali Empire erected grand monuments and academies that attracted scholars from Egypt, Spain, and Morocco.

This prime location, though, also made Timbuktu a tempting target for warlords. As the Mali Empire waned, Songhai rose to power. In 1468, the Songhai king conquered Timbuktu, burning buildings and killing scholars. Still, intellectual life eventually bounced back. Under King Askia Mohammed Toure, the city experienced a golden age. He embraced learning and reversed previous regressive policies.

Most of Timbuktu’s residents and its rulers were Muslim. The city’s scholars delved into Islamic studies as well as subjects like mathematics and philosophy. Timbuktu’s libraries housed Greek philosophy next to works by local historians, scientists, and poets. One of the most notable scholars, Ahmed Baba, defied prevailing views on various issues, including smoking and slavery.

The thriving trade of gold and salt fueled Timbuktu’s transformation into a learning center. Soon, the manuscripts created there became the highly prized commodities. Using paper from Venice and vibrant local inks, Timbuktu’s scribes produced texts in Arabic and local languages. These books, adorned with elegant calligraphy and geometric designs, were coveted by society’s elite.

The prosperity crumbled in 1591 when the Moroccan king captured Timbuktu. Moroccan forces imprisoned scholars like Ahmed Baba and confiscated their collections. Over the following centuries, Timbuktu endured numerous conquests. Sufi Jihadists destroyed many non-religious manuscripts in the mid-1800s. By 1894, French colonial forces had taken control, plundering more manuscripts and shipping them to Europe. With French as the new official language, many in Timbuktu grew unable to read the remaining Arabic texts.

Despite these setbacks, Timbuktu’s literary tradition survived underground. Families built secret libraries, buried books in gardens, stashed them in deserted caves, or the desert itself. These invaluable manuscripts scattered across villages, where everyday citizens protected them for centuries. Even as desertification and war plunged the region into poverty, families clung to these ancient texts.

From the 1980s to early 2000s, Abdel Kader Haidara, a dedicated Timbuktu scholar, worked tirelessly to recover hidden manuscripts from northern Mali. But the 2012 civil war in Mali posed a new threat, prompting the evacuation of most of these manuscripts to Bamako. Their future remains precarious, facing both human and environmental dangers.

These books are our best and often sole sources on pre-colonial history in the region. Many of these priceless manuscripts remain unread by modern scholars, with countless more still lost or concealed in the desert. The ongoing efforts to protect them carry immense stakes, preserving centuries of history and the enduring struggle to safeguard that heritage.