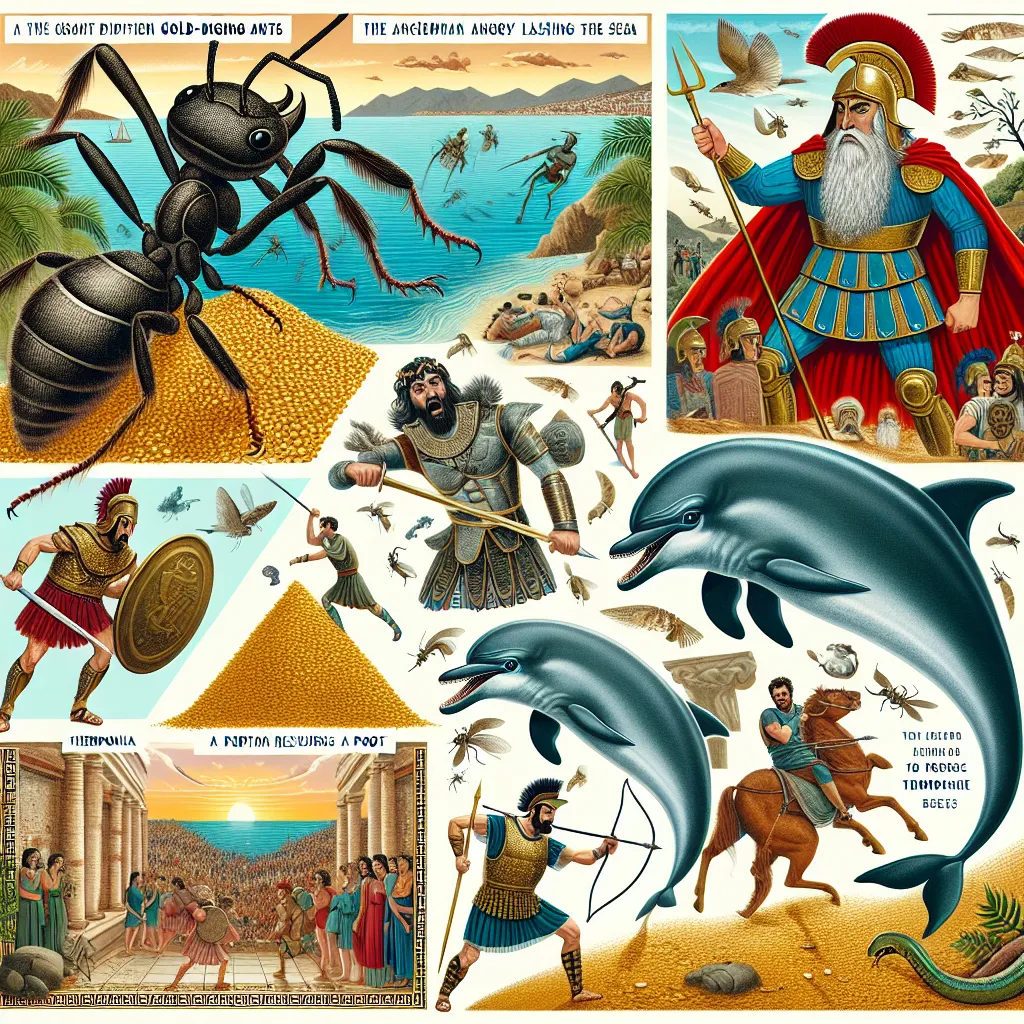

Giant gold-digging ants, an angry king whipping the sea, and a heroic dolphin saving a poet—these are just some of the wild stories you can find in The Histories by Herodotus. This 5th-century BCE Greek writer didn’t just change the way we record history; he revolutionized it. Before him, people mainly saw history as a mere rundown of events, often blaming or crediting the gods for everything.

Herodotus, however, craved a deeper understanding. He sought to explain why things happened, looking at events from multiple perspectives. Although he was Greek, his hometown of Halicarnassus was part of the Persian Empire. Growing up during tumultuous times of war between the mighty Persians and the relatively small Greek city-states, he became obsessed with uncovering the roots of these conflicts.

According to Herodotus, the Persian Wars kicked off in 499 BCE, ignited by the Athenians assisting Greek rebels under Persian rule. By 490 BCE, Persian King Darius wanted to crush Athens for this, but the Athenians pulled off a shocking victory at the Battle of Marathon. Ten years later, Darius’s son Xerxes tried to take all of Greece by force. Xerxes’s massive army faced fierce resistance from a small Greek force led by 300 Spartans at Thermopylae. The Spartans, led by King Leonidas, were ultimately defeated but became eternal symbols of bravery. Later, the Greek navy tricked and defeated the Persian fleet near Athens, forcing Xerxes to retreat and never return.

Herodotus didn’t just narrate events; he gathered stories and achievements from across the Mediterranean, preserving them before they vanished. His famous opening line, “Herodotus, of Halicarnassus, here displays his inquiries,” set the tone for a work filled with diverse tales—some factual, some fantastical. From Persian court intrigues to flying snakes in Egypt and even practical advice on catching crocodiles, his curious mind covered it all.

Herodotus used a method he called “autopsy,” meaning “seeing for oneself.” He relied on eyewitness accounts, hearsay, and traditions. Then he applied reason to piece together what likely happened. His work was initially meant to be read aloud, with each of the 28 sections taking about four hours to narrate.

Despite some flaws—like occasionally favoring Greek accounts and sometimes falling for tall tales—Herodotus’s methodology set the foundation for modern history. Some of his outrageous claims, like gold-digging ants, now make a bit more sense; he probably misunderstood the Persian word for marmot, which does spread gold dust while digging.

Herodotus wasn’t perfect, but for pioneering a whole new way of recording history, he earned the title given by Roman author Cicero: “The Father of History.” His creative approach and dedication paved the way for all future historians, showing that even with all our mistakes and biases, seeking the truth is worthwhile.