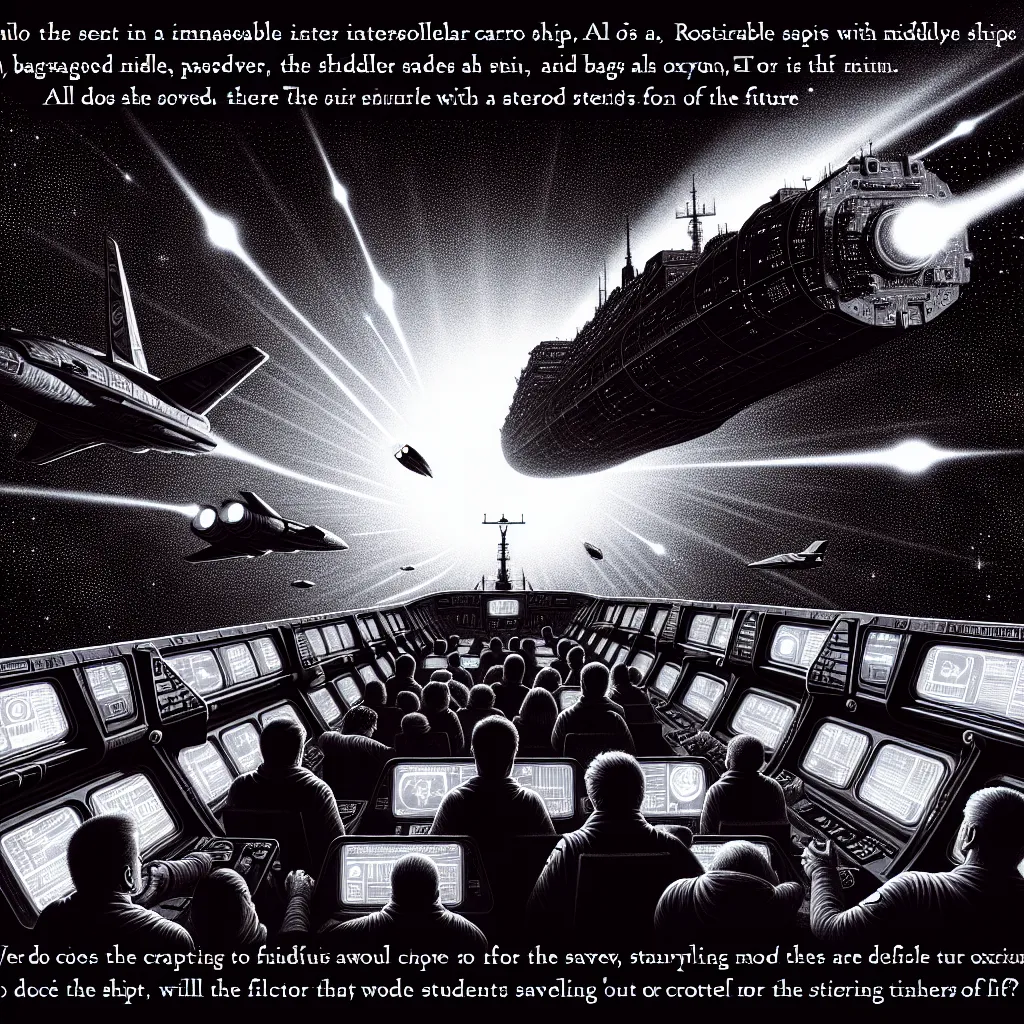

You are the captain of the Mallory 7, an interstellar cargo ship. On your way to the New Lindley spaceport, a distress call comes in. An explosion has occurred on the Telic 12, and its passengers are running out of oxygen. Quickly, you set a course to help. The Telic 12 is transporting 30 middle-aged people from Earth’s poorest districts to the labor center on New Lindley to get jobs.

But then, another distress call. A luxury cruiser called the Pareto has lost a thruster and is heading towards an asteroid belt. Onboard are 20 college students heading for a vacation, and without your intervention, they’re doomed. You only have time to save one ship. Which one will it be?

This dilemma isn’t just about space—it mirrors tough decisions we face on Earth with scarce resources like organs or vaccines. One theory that deals with this is utilitarianism, which suggests you should choose the action that creates the greatest happiness. But what defines happiness? Some say it’s pleasure minus pain, others say it’s fulfilling desires. Regardless, saving 30 lives might create more happiness than saving 20. But is it just about the number of lives?

Let’s consider life years. If the students are 20 years old on average and could live to 80, saving them nets 1,200 life years. If the workers are 45, saving them nets 1,050 life years. So, saving the students might actually promise more overall happiness due to longer potential lives.

Feeling cold about these calculations? Philosopher Derek Parfit suggests prioritizing the worse off. Benefits to those less fortunate matter more than equivalent benefits to the well-off. Earth is rife with economic inequality. The vacationing students are surely among the well-off, while the workers are disadvantaged. They’ve likely endured more hardship, so perhaps they’re more deserving of rescue. But are they truly worse off compared to younger students who have lived less?

Alternatively, philosopher John Taurek argued that numbers shouldn’t count. Each person’s life has equal value, so deciding by a coin flip might be the fairest. It treats all individuals equally, offering each an equal chance of rescue. Could any passenger argue they’re being treated unfairly by such randomness?

This might seem arbitrary, but it’s an approach that recognizes everyone’s equal worth. How the rescued or left-behind feel about it is another dilemma altogether, one that’s equally tough to navigate.