COVID-19, officially known as SARS-CoV-2, has taken the world by storm, though the U.S. hasn’t seen the worst-case scenario. Hospitalization rates remain high, showcasing the unique and concerning nature of this virus. What makes SARS-CoV-2 stand out from common colds, seasonal flu, and even other deadly viruses like SARS, MERS, or Ebola?

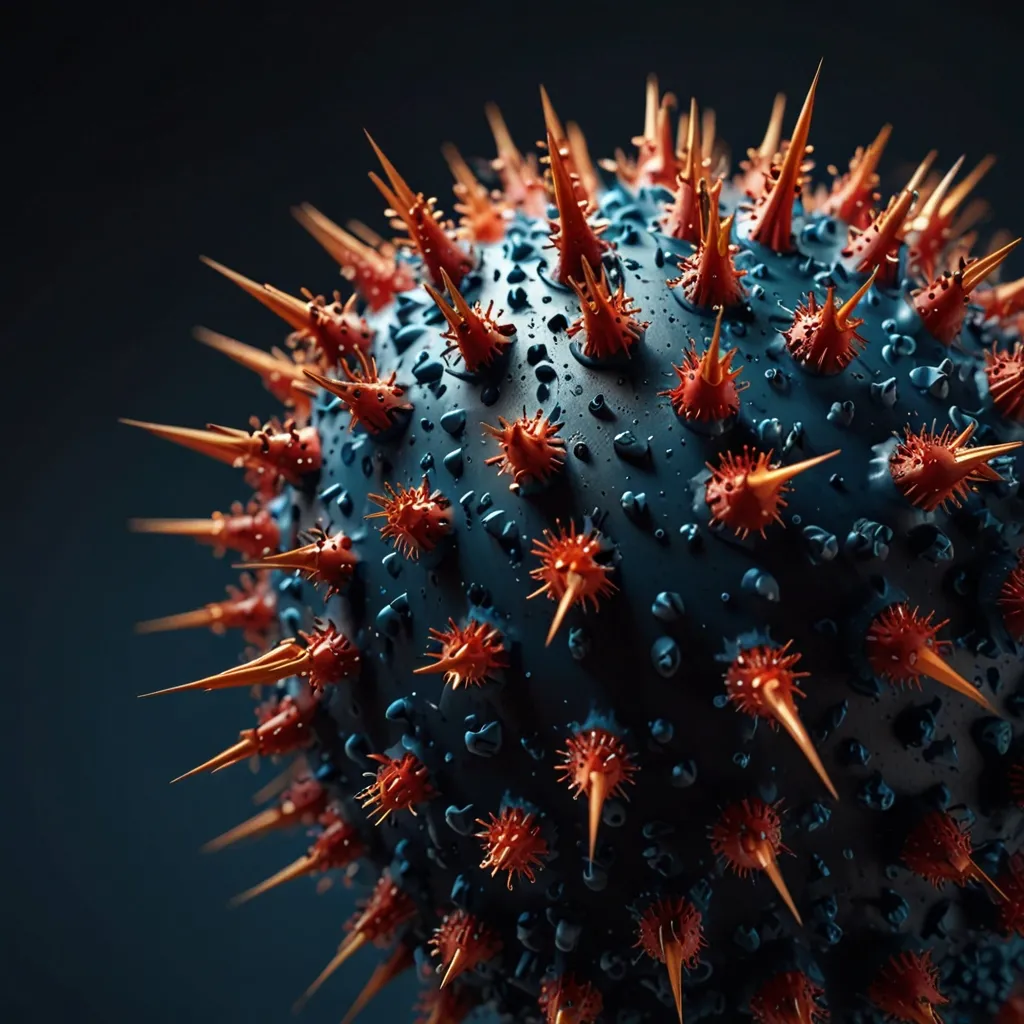

This virus is a ‘Frankenstein’ of sorts, combining the most dangerous properties of various viruses. Despite its tiny size—so small that 100 million could fit on a pinhead—it has a significant impact. Microscopically examined, a coronavirus particle consists of genes encased in a protein coat and a fatty lipid sphere. Unlike living organisms, viruses don’t move or metabolize independently but rely on invading cells to reproduce. This reliance makes them particularly devious, evolving quickly through mutations. The RNA in coronaviruses is particularly unstable, leading to faster and more frequent changes.

Viruses aim to invade as many cells as possible to maximize replication. The unique structure of SARS-CoV-2 reveals its clever strategy. It features spikes that latch onto the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on certain cells like those in our lungs and kidneys. This spike interaction is stronger in SARS-CoV-2 than in its SARS predecessor, making it highly infectious. Essentially, fewer particles are needed to start an infection compared to other viruses.

People with type 1 or type 2 diabetes produce more ACE2, making them more susceptible to severe COVID-19. Once inside a cell, SARS-CoV-2’s RNA hijacks the cell’s machinery, tricking it into making more copies of the virus. Unlike other RNA viruses, SARS-CoV-2 has a spell-check mechanism, allowing it to reduce replication errors, making it more robust and difficult to combat.

As the virus replicates, immune responses can make it hard for us to breathe, often making our body’s reaction more lethal than the virus itself. SARS-CoV-2 infects both upper and lower respiratory tracts, a rarity that contributes to its high contagion and severity. This dual infection pattern means it spreads easily during the initial mild phase, before moving to the lungs where symptoms become severe.

Highly lethal viruses like Ebola or MERS tend to spread less because they incapacitate their hosts quickly. SARS-CoV-2, however, remains mild long enough to spread widely, likened to a twisted serial killer that needs you alive to spread further. The virus prefers the respiratory tract because few internal organs are so exposed to the air, making it easier for the virus to attach.

Though not the flu, SARS-CoV-2 is deadlier and spreads more effectively. The fatality rate is significantly higher than the flu, and it’s more contagious, capable of infecting more people faster. Hospitalization rates for COVID-19 victims are also much higher. Reports from New York and China showed that 20% of symptomatic people needed hospitalization, compared to only 1.4% for flu victims.

The virus likely originated from bats, potentially crossing to humans directly or through another species. Despite its ‘perfect’ design that makes it seem engineered, extensive scientific analysis confirms it’s a natural virus.

Without a cure or vaccine, prevention is key. The virus is fragile outside the body, so soap and water are highly effective in destroying it. Alcohol-based solutions (with over 65% alcohol) also work, but household liquors won’t do the trick. Heat can kill the virus, so thoroughly cooking food is advisable. It lasts up to three days on surfaces like metal and plastic, so washing hands regularly is critical. Avoid touching your face and be cautious when cleaning surfaces, as dusting could release the virus into the air.

Masks, especially N95s, can offer protection by filtering out viruses. However, they should be reserved for healthcare workers. Public mask-wearing has been linked with lower infection rates in some societies, suggesting a potential benefit.

The best collective action is to reduce the burden on healthcare systems by staying home and practicing social distancing. This virus will eventually pass, and in the future, it might become just another cold or flu. Until then, stay safe, wash your hands, and follow public health advice to protect yourself and others.