Big tech companies are bigger and more influential than ever, and with that power, there’s a growing call for antitrust litigation. But the harsh reality is, breaking up these tech giants isn’t likely. Let’s explore why that’s the case by diving into some historical context and legal nuances.

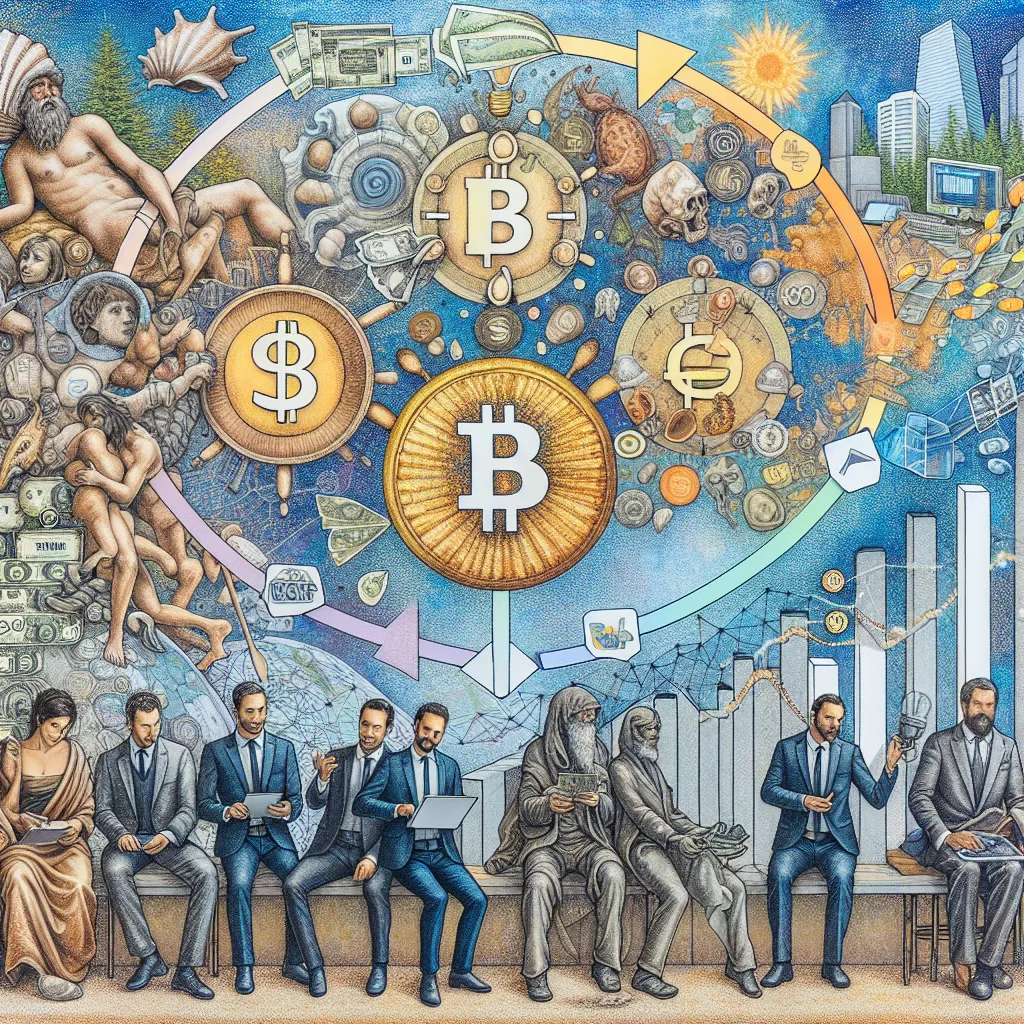

To understand modern monopolies, we need to travel back 150 years to the end of the American Civil War. Post-war America saw an explosion of new technologies like telegraphs for instant communication and expanding railroads, which fueled massive business growth. Companies like Standard Oil, led by John Rockefeller, grew immense. Rockefeller’s strategic buyouts, including the infamous Cleveland Massacre, allowed Standard Oil to control a staggering 90% of America’s oil.

It took the political will of President Roosevelt and a historic antitrust lawsuit to take down Rockefeller’s monopoly. By 1911, Standard Oil was found guilty of violating the Sherman Antitrust Act. This was the first major case that set the precedent for antitrust action in America. Roosevelt pursued 45 such cases, and his successor, William Howard Taft, nearly doubled it.

However, the view on antitrust started shifting around the 1970s. President Reagan, influenced by scholar Robert Bork, redefined the focus. Bork argued that the size of a company wasn’t the issue, but rather whether consumers benefited. This idea, known as Consumer Welfare, changed how antitrust cases were approached. Under this framework, big isn’t bad as long as customers are happy.

Now, let’s apply this to today’s tech giants: Apple, Google, Amazon, and Facebook. Each of these companies dominates their space, but are they monopolies? Legally, dominance isn’t enough; they need “durable market power.” Google, with 92% of the search engine market, isn’t exploiting its users because hopping to another search engine is just one click away. Similarly, Amazon’s vast e-commerce lead depends on customer satisfaction and competitive pricing.

Apple presents a more complex case. With only 20% of the smartphone market, it doesn’t look like a monopoly at first glance. But Apple’s control over its iOS ecosystem and the 30% commission on its App Store raises eyebrows. By forcing developers into its pricey store, Apple is inflating prices for consumers. There’s an ongoing lawsuit addressing this, but even if Apple loses, breaking up iOS isn’t practical—lowering commissions is likely the best outcome.

Facebook, however, might be the one to watch. Its acquisition of Instagram, which was a burgeoning competitor, seems problematic. Facebook’s main power lies in its ability to exploit user data privacy, which remains contentious.

Ultimately, none of these tech giants are clear-cut cases for breakup under current antitrust laws. The big question is whether Reagan’s antitrust framework is outdated for today’s trillion-dollar tech landscape. Time will tell if we see any legal shifts, but for now, breaking up big tech isn’t on the horizon.

Stay tuned and stay smart.