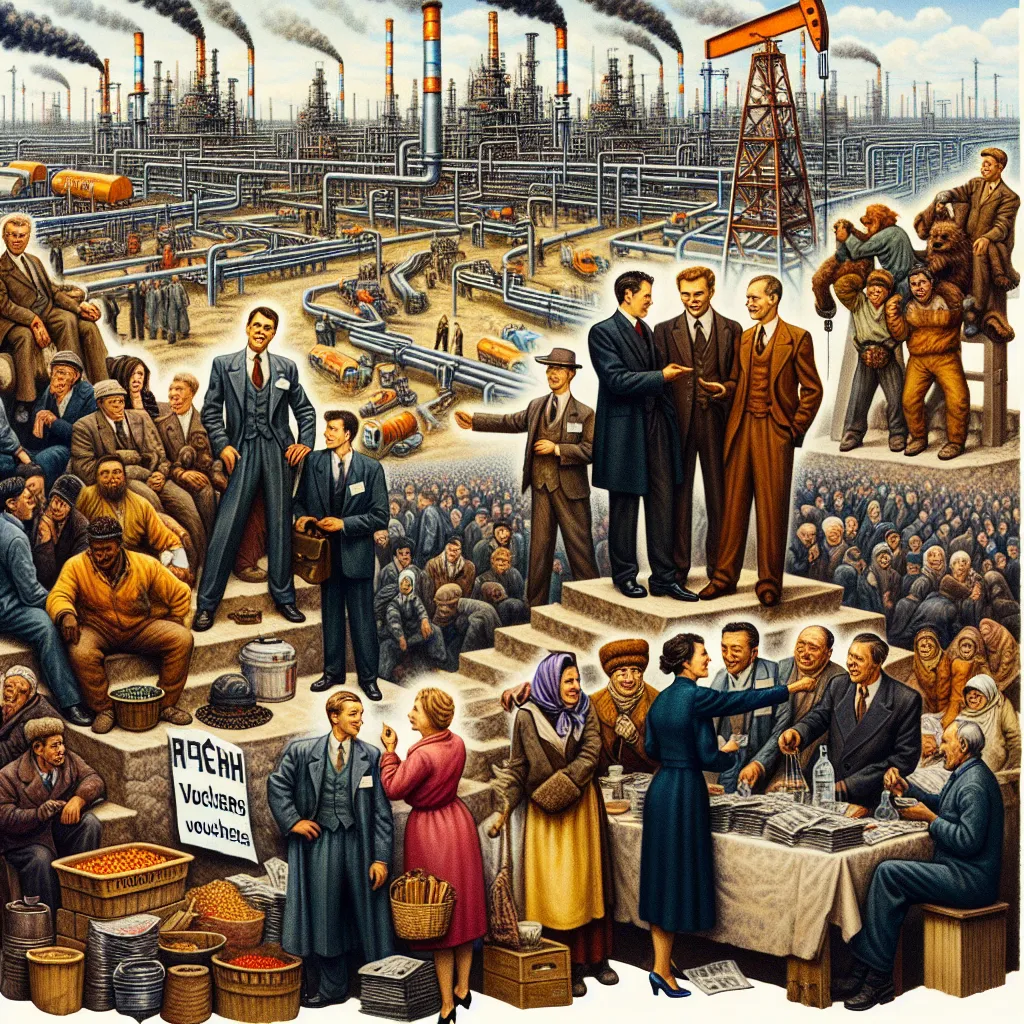

After the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia’s wealth ended up in the hands of a few businessmen known as the New Russians or oligarchs. They took control of more than half the Russian economy, including its massive oil industry. Today, let’s dive into how this transition unfolded, especially with regard to one of Russia’s largest oil companies, Lukoil.

On Christmas Day in 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev announced on national television his resignation as president of the USSR. The bigger shock came the next day when the Soviet Union was dissolved, and Boris Yeltsin took over as the Russian president. Yeltsin envisioned rapid and drastic reforms. He aimed to transition Russia to a free-market economy as quickly as possible. Supported by funds from the Bush Senior administration and research from a Harvard think tank, Yeltsin launched an economic shock therapy.

Yeltsin’s plan included removing price and currency controls, lifting barriers on international trade, and most importantly, privatizing the country. Instead of setting up a proper transition infrastructure, he opted for a simple solution: issuing vouchers to every Russian citizen. These vouchers could be exchanged for shares in newly privatized businesses. The idea was that workers would convert their vouchers for shares in the companies they worked for, benefiting from their success.

The plan sounded good on paper but was easy to abuse. Most Russians at the time had no clue about capitalism or shares. After 1991, many people were just relieved to receive their wages, even if delayed by a few months. These vouchers were worth about $30, approximately a month’s wage. Most people sold them for cash to feed their families or buy much-needed luxuries like a refrigerator.

Very few Russians in 1991 were educated or wealthy enough to capitalize on these vouchers. The ones who could, often through underhanded methods, became very wealthy. For example, Sibneft’s owner Roman Abramovich stopped paying his workers’ salaries for several months, then offered to buy their shares. Some newly privatized oil companies even issued more shares to dilute the value, using shell companies so that ordinary people didn’t realize what was happening.

A prime example of this wealth transition is Vagit Alekperov. Born in present-day Azerbaijan, Alekperov’s father was an oil worker. Alekperov studied engineering and moved to Western Siberia, where large oil fields were discovered in the early ’60s. In 1983, he became the director of oil production in Kogalym and dramatically boosted their output.

His performance caught Moscow’s attention, and he became the deputy minister of oil and gas. As the Soviet Union neared its end, he built favor with Yeltsin, who allowed him to consolidate Russia’s oil industry. Alekperov created Lukoil by merging three significant oil producers. Under the privatization scheme, the state kept a third of the shares, workers received a third through vouchers, and the final third was for outside investment. Alekperov and other oligarchs quickly bought out the workers’ shares and also those held by the government when Yeltsin needed money for reelection.

Lukoil, suffering from inefficient Soviet-era equipment, made a deal to sell 70,000 barrels of oil per day to Chevron and used the revenue for a $700 million loan from a Japanese company. With new equipment, Lukoil became highly profitable, even during the oil crash of 1998. The main benefactors were the oligarchs, who moved much of their wealth outside of Russia into foreign stocks and real estate. Despite low oil prices in recent years, Russia’s oil industry isn’t going anywhere. Oil remains the lifeblood of the economy, meaning oligarchs have decades of revenue ahead, while everyday Russians, unfortunately, don’t share the same outlook.

And that’s the story of how Russia’s wealth got concentrated in the hands of a few following the Soviet Union’s collapse, leaving the average Russian grappling with the repercussions.