Most stories told about Africa’s history begin and end with European exploration, as if the continent were a blank slate waiting for someone to draw its story. Growing up, I remember being taught that Africa was “discovered” as though it had been invisible. But what if I told you that long before any colonial official set foot on the continent, there were kingdoms with universities, advanced craftsmen, bustling trade routes, and thriving cities that could rival anything in medieval Europe? Let’s revisit five of these African kingdoms whose legacies force us to rethink what we thought we knew.

Ask yourself: How different would global perceptions be if the grandeur of these kingdoms took center stage in world history textbooks instead of the conquest narratives?

“When lions have historians, the hunters will cease being heroes.” – African Proverb

Consider the Kingdom of Benin. By the time Portuguese merchants first anchored off its coast in the late 15th century, Benin City was already renowned for its sophisticated urban planning, wide streets, and moats deeper than the height of a man. The true marvel, though, was its art. The Benin Bronzes—stories in metal—documented everything from royal processions to diplomatic missions. Crafted with such skill, these bronze plaques still puzzle modern metallurgists. In the late 19th century, when British troops sacked Benin, they carted off thousands of these treasures. Today, these artifacts sit in museums worldwide, symbols of both cultural brilliance and cultural theft.

Isn’t it striking that it took so long for international conversations about restitution to take root? In truth, the Bronzes are not just art—they’re a living record, a challenge to ideas of African primitiveness that persist to this day.

“Until the lion tells his side of the story, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” – Chinua Achebe

Move west, and we reach the sand-swept city of Timbuktu in the Mali Empire. Mention Timbuktu and most people picture a city far away, almost mythical in obscurity. But in the 14th and 15th centuries, it was a bustling hub of learning and commerce. Universities and libraries buzzed with scholars from across North Africa and the Middle East. Historical manuscripts—on astronomy, mathematics, jurisprudence, and poetry—were painstakingly copied and preserved. It’s estimated there were more books in Timbuktu at its zenith than in much of Europe at the same time. If you ever wondered whether Africans valued literacy, just remember that libraries and private collections here held up to 700,000 manuscripts. Today, painstaking efforts by families and local organizations are returning some of these ancient works to light, proof of a scholarly tradition that survived even war and extremism.

Ever asked yourself: Why were European explorers so quick to discount African achievements? Part of it lies in the refusal to accept a vibrant intellectual life outside Europe’s borders. Timbuktu unravels that myth—book by book, manuscript by manuscript.

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” – Nelson Mandela

Travel southeast and you find Great Zimbabwe. Imagine a city built without mortar, its walls swirling in elegant curves that loom over the savannah. Great Zimbabwe was home to up to 18,000 people at its height—its walls crafted with such precision that even today, centuries later, they still stand. European visitors in the 19th century simply could not accept that local people built this marvel; instead, they concocted wild theories about lost white civilizations or Biblical kings. But every stone tells the true story: Africans engineered these cities, and they thrived on gold trade and skilled governance.

Why do myths linger so long after they’ve been debunked? The stubbornness of the colonial gaze shaped not only popular imagination but also academic research for generations, casting doubt on African ingenuity even in the face of overwhelming evidence.

“History is written by the victors.” – Winston Churchill

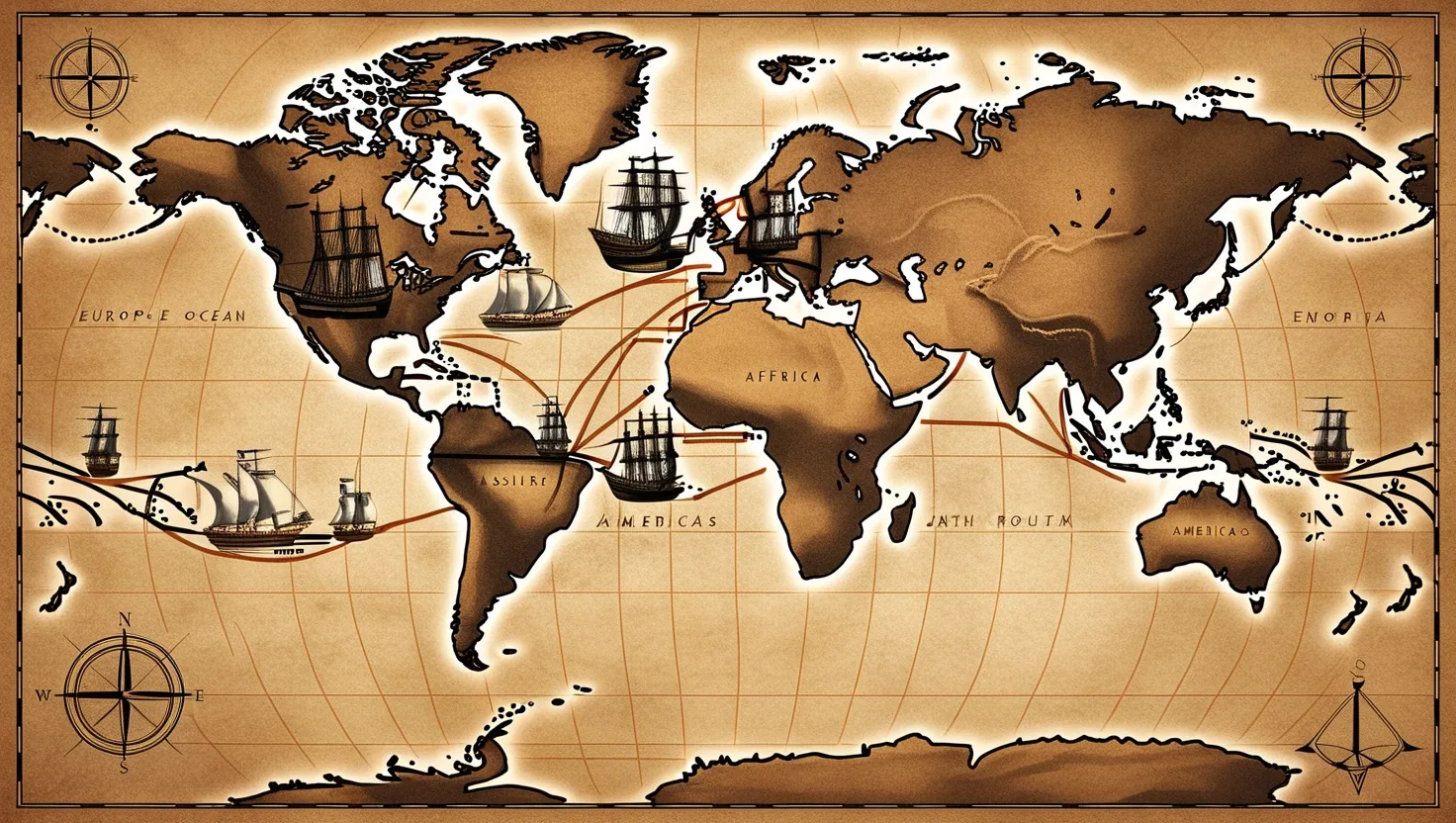

Now, picture the Swahili Coast—city-states like Kilwa, Mombasa, and Zanzibar linked by trade winds and the ceaseless churn of Indian Ocean commerce. These were cosmopolitan societies fluent in several languages—Swahili itself is a blend, shaped over centuries of contact. Their harbors welcomed Chinese, Indian, and Persian traders, who left porcelain, glassware, and even coins in the market stalls. The Swahili traded gold, ivory, and spices, forging connections that stretched from East Africa to Indonesia and beyond. Archaeology confirms this vast network: Chinese ceramics, Persian perfume bottles, and Indian beads unearthed in tombs, evidence of a world that was always interconnected.

Can you recall learning about African maritime cultures in school? Most curricula skip over the sea routes, focusing only on caravans and deserts. But the Swahili city-states flip the narrative; they show how African societies were gatekeepers—not just recipients—of global trade.

“I am not African because I was born in Africa but because Africa was born in me.” – Kwame Nkrumah

As we move to the Ethiopian highlands, the Kingdom of Aksum comes into view—a power so substantial it was considered a peer to Rome and Persia. By the 4th century, Aksumite kings issued gold coins stamped with their own faces and ruled territories across the Red Sea. The kingdom’s obelisks, carved from single slabs of granite and towering nearly 80 feet, required engineering know-how that still impresses today. Aksum converted to Christianity even before many European nations, and its churches and monasteries became safe havens for learning after the fall of Rome. The kingdom’s influence stretched as far as southern Arabia, its stelae standing as silent witnesses to a civilization that shaped the Horn of Africa and beyond.

Ever wondered why we talk about Roman or Persian empires, but rarely about Aksum in the same breath? The reasons are complex, bound up with how history is curated. Aksum’s legacy isn’t just monumental—it is a reminder that Africa stood at the crossroads of religions, ideas, and power long before colonization.

So what do these kingdoms—Benin, Mali, Great Zimbabwe, the Swahili city-states, Aksum—offer us today? For one, they force us to critically assess the selective memory of colonialist storytelling. These narratives often sidelined Africa’s past, painting it as a place without history, waiting to be shaped by outsiders. But each kingdom tells a different story: of rulers shaping law and custom, artists and engineers pushing creative boundaries, scholars illuminating the night with new ideas, merchants connecting continents.

Let me ask you: How might Africa look today if its historical achievements were as widely celebrated as those in Europe or Asia? Would restitution debates have started sooner? Would stereotypes of “underdevelopment” ever have gained ground?

The histories of these kingdoms are not lost—they’re resurfacing in museum exhibitions, school curricula, and the growing movement to return stolen artifacts to their origins. They invite us to look beyond the familiar stories and to ask tougher questions about who gets to tell the past. Their ruins and artifacts aren’t just reminders of former glory, but blueprints for what a future rooted in truth and dignity can look like.

“A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.” – Marcus Garvey

As we close this chapter, take a moment to reflect: The next time you hear about African history, will you picture only the familiar images of colonization and hardship, or will you remember the thriving universities of Timbuktu, the engineers of Great Zimbabwe, the artists of Benin, the traders of Kilwa, and the empire-builders of Aksum? The answer can shape how we see the world and each other. Africa’s kingdoms did more than shatter colonial myths—they built new foundations for understanding, ones worth exploring, honoring, and sharing.