Economic ideas shape the world in powerful, sometimes chaotic ways. It’s tempting to believe that intellectual frameworks, crafted by brilliant minds, will guide societies straight toward prosperity. Yet, as history shows, theories often crash into reality—and when the real world refuses to cooperate, the consequences are anything but academic.

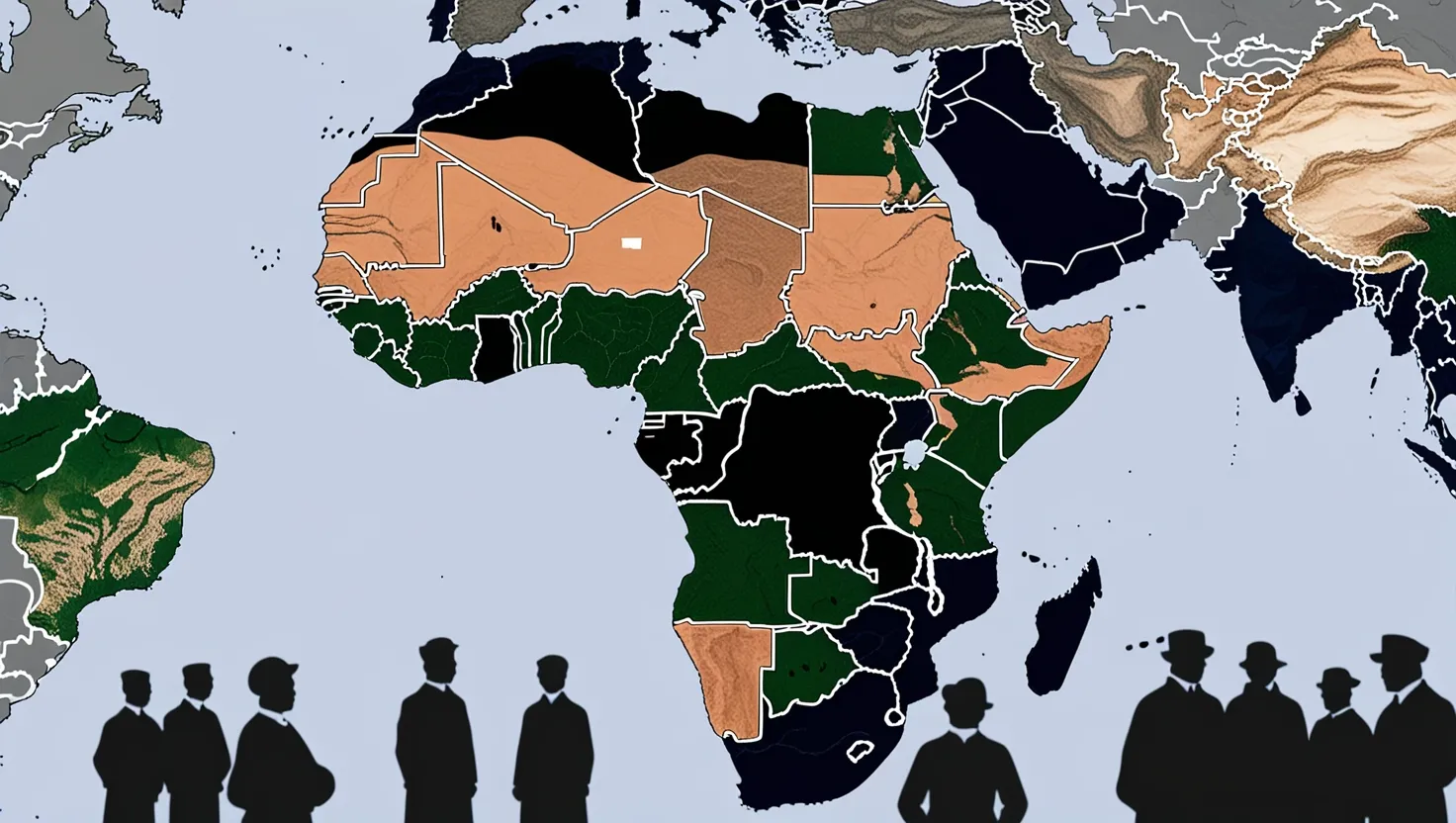

When I think of mercantilism, I picture gold-laden ships and bustling colonial ports. This 16th-century theory was built on the belief that national wealth meant accumulating precious metals. So, governments created policies that hoarded gold and restricted imports, assuming more exports would lead to dominance. Colonies became mere supply engines, feeding raw materials into the mouths of European industry and buying back finished goods. But did anyone ask, what happens when colonies stop playing along? Mercantilism ignored the human desire for autonomy and underestimated the costs of making people work for your bottom line. Colonists eventually rebelled, and inefficiency spread through rigid market controls. Protectionism still rears its head today, but what remains is a caution: one person’s gain isn’t always another’s loss. Can economic growth really be fueled by shutting others out?

Adam Smith famously wrote, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” Yet his theory of the invisible hand ran into its own limits. While Smith saw markets as self-correcting machines, real markets have more moving parts than any one individual can control or predict. The crash of ’29 and the great depression that followed were vivid reminders that markets do not automatically get it right. Sometimes, you need more than invisible hands—you need visible ones stepping in to keep things from falling apart.

Then there was the Gold Standard, hailed as the guardian of monetary stability. The logic was simple: tie a currency’s value directly to gold, and you prevent runaway inflation and keep things predictable. But what happens when predictability itself becomes problematic? During the Great Depression, governments found themselves handcuffed—unable to adjust currency supply to support demand or investment. Britain’s 1931 break from the standard was a watershed moment, showing that flexibility often trumps rigidity. The shift to fiat currencies, though seen as risky by some, has allowed societies to respond faster to crises—proof that what feels secure on paper can leave you paralyzed when times really get tough. Does economic stability mean more rules, or more room to adapt?

“Markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.” These famous words, attributed to John Maynard Keynes, ring especially true when discussing the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). This late-20th-century theory assumed that markets always price assets fairly because everyone acts rationally and all information gets absorbed instantly. That sounds appealing; it suggests that you can’t “beat” the market because it’s already accounted for everything. Yet, the 2008 financial crisis exploded that notion. The housing bubble swelled as people assumed prices would always rise, herding together in reckless optimism. Entire financial institutions collapsed, revealing that markets can ignore facts, dismiss risk, and follow crowds off a cliff. There’s power in collective belief, but sometimes, the crowd gets it wrong. If the EMH promised fairness, why do markets still create winners and losers?

The next theory, labor determines value, comes directly from the writings of Karl Marx. Communism’s architects built economic plans on this foundation: what something’s worth comes down to how much labor goes into making it. But what if people want things for reasons other than the hours put in? Soviet planners tried to set prices and output according to this model, only to discover empty shelves, black markets, and poor-quality goods. Human desire proved impossible to quantify. People wanted variety, advanced technology, and choices—not just what fit a formula. Economic planning collapsed, not only under inefficiency, but under frustration and unmet demand. Can human preference ever be engineered through numbers alone?

Let me pause and ask, why do theories that sound so good in classrooms spiral out of control in practice? Is it human error, or is it something about reality that theory cannot reach?

Trickle-down economics swept through policy-making in the 1980s. The logic sounded bulletproof on paper: cut taxes for corporations and high earners, and wealth will flow down to everyone as the economy blooms. Yet, after decades, what shows up in the numbers is rising inequality. The riches didn’t “trickle down” quite as expected; instead, they pooled at the top. While proponents insisted this approach encouraged investment, critics pointed out that gains in productivity benefitted mostly those with capital, not working families. The appeal persists—the promise that growth for some means growth for all—but experience calls it into question. To quote Franklin D. Roosevelt: “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

Looking at history, I often wonder, why do so many economic ideas falter when put into practice? Are we missing crucial facts? Or are we ignoring the unpredictability that comes with real people interacting in real systems?

One lesser-known example: Keynesian theory, which holds that government spending can revive demand during downturns, worked wonders after World War II. But as prosperity grew, some worried about government’s expanding role and argued that inflation, not unemployment, deserved focus. This pivot, driven more by political desire than objective results, led to periods of economic stagnation with stubbornly high joblessness. The lesson: theories become policy, and policy gets tangled in power struggles.

It’s striking how some theories linger long after being disproven by experience. The idea that free markets always produce full employment persists in textbooks, even as labor data paint a different picture. Productivity rises, wealth accumulates, yet not everyone shares equally. Why do we cling to outdated models?

Sometimes, the major misstep isn’t just miscalculation—it’s overconfidence. Irving Fisher, a celebrated economist, predicted stock prices had reached a “permanently high plateau” days before the 1929 crash. Experts in the years leading up to the 2008 recession dismissed warnings about subprime mortgages. Ravi Batra predicted a 1990 recession that never came. Economists, like the rest of us, are fallible.

This brings me to a crucial point. Economic systems are human systems. They aren’t just numbers on a page but collections of belief, hope, and fear. Theories are only blueprints—not guarantees. When ideas fail, what’s revealed isn’t just a technical flaw. It’s a reminder that models must serve people, not just perfection in abstraction.

“Economics is extremely useful as a form of employment for economists.” This dry observation from John Kenneth Galbraith signals the gap between theory and reality. It’s easy to become attached to big ideas. It’s harder to accept that sometimes, those ideas must yield to facts on the ground.

When I think about what we’ve learned, one thing stands out: adaptation is more valuable than rigid adherence. Economic thought lives best when it admits complexity, human variety, and the limits of prediction. No single framework can account for everything—from natural disasters and sudden innovation to political upheaval and cultural shifts.

In your own decisions—whether investing, planning, or simply trying to understand the world—ask yourself: whose reality does this theory describe? Does it leave room for surprise, for error, for people acting differently than expected? Economic failure isn’t just a matter of wrong numbers. It’s an invitation to question and improve.

And so, as we go forward, consider the words of Winston Churchill: “Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.” Economic ideas will continue to collide with reality. Our job is not to avoid mistakes, but to learn and adapt, always remembering that the heart of every system is the people it serves.

How might the next big idea fare when it meets the complexities of real life? Only time will tell, but history suggests we should remain critical, flexible, and ready to modify our assumptions. After all, the only constant is change.