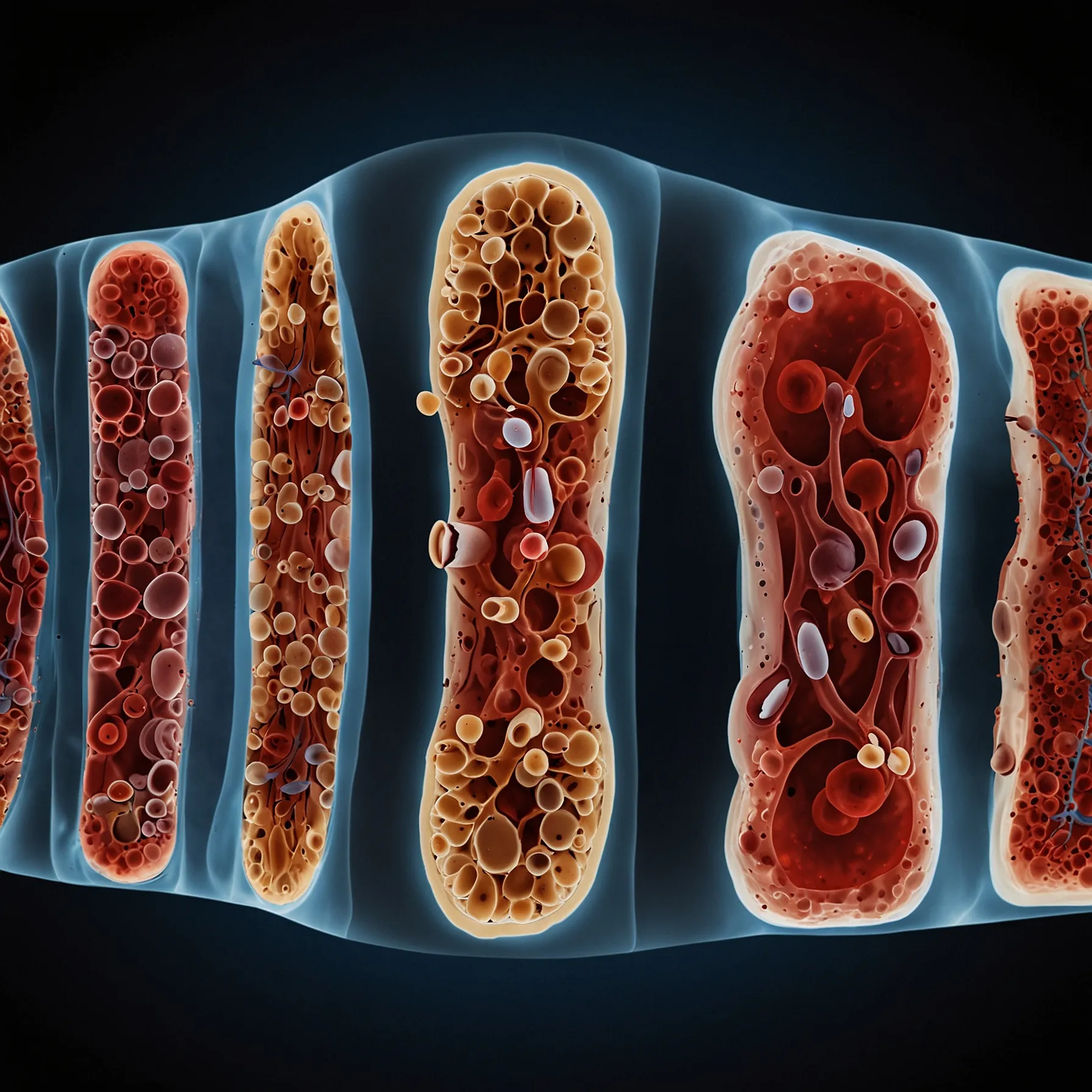

At any moment, trillions of cells are moving through your blood vessels, sometimes making a full circuit of your body in just a minute. These cells all originate deep within your bones. While bones may seem solid, they are actually porous inside, allowing blood vessels to enter through small openings. Inside most large bones is a hollow core filled with soft marrow, which contains fat and other supportive tissue but, most importantly, blood stem cells.

These blood stem cells are constantly dividing. They can turn into red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets, sending hundreds of billions of new blood cells into circulation every day. These new cells enter the bloodstream through tiny capillaries in the marrow, eventually making their way into larger blood vessels and out of the bone. If there’s a problem with your blood, it usually traces back to the bone marrow, where blood cancers often begin due to genetic mutations in the stem cells.

For patients with severe blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma, an allogeneic bone marrow transplant often offers the best chance for a cure. This procedure replaces the patient’s bone marrow with that from a donor. Blood stem cells are extracted from the donor, either by filtering them out of the bloodstream or directly from the hip bone. The recipient undergoes high doses of chemotherapy or radiation to kill the existing marrow, weakening the immune system to avoid attacking the transplanted cells. The donor cells are then infused into the patient through a central line. Chemokines on the stem cells help them find their way back to the marrow, where they begin to multiply and produce new, healthy blood cells.

A small number of blood stem cells can regenerate an entire body’s healthy marrow. Sometimes, new immune cells from the donated marrow can help eliminate remaining cancer cells in a process called graft-versus-tumor activity. However, bone marrow transplants come with risks, such as graft-versus-host disease, where the new immune system attacks the patient’s organs. This condition affects about 30–50% of non-twin donor recipients. Immunosuppressants or removing certain immune cells from the donated sample can reduce this risk, but the new immune system may still reject the donor cells.

It’s vital to find the best possible donor match to minimize these risks. Key regions of the genetic code determine how the immune system recognizes foreign cells. If these regions match well between the donor and recipient, the likelihood of successful acceptance increases. Since these genes are inherited, siblings often make the best matches, but many patients don’t have a compatible family member and turn to donor registries. Signing up for these registries typically involves a simple cheek swab to test for genetic compatibility.

Donating bone marrow can be as simple as giving blood for many, offering a chance to save someone’s life with a renewable resource.