History, we like to believe, is an organized record of the past—neat, complete, and constructed intentionally by careful scholars. But have you ever wondered how many defining moments in our understanding of ancient people surfaced not from scholarly design, but by pure accident? The truth is, destiny loves a twist, and some of the most profound archaeological revelations arrived through mundane mishaps, serendipitous stumbles, or even a bit of good old-fashioned curiosity.

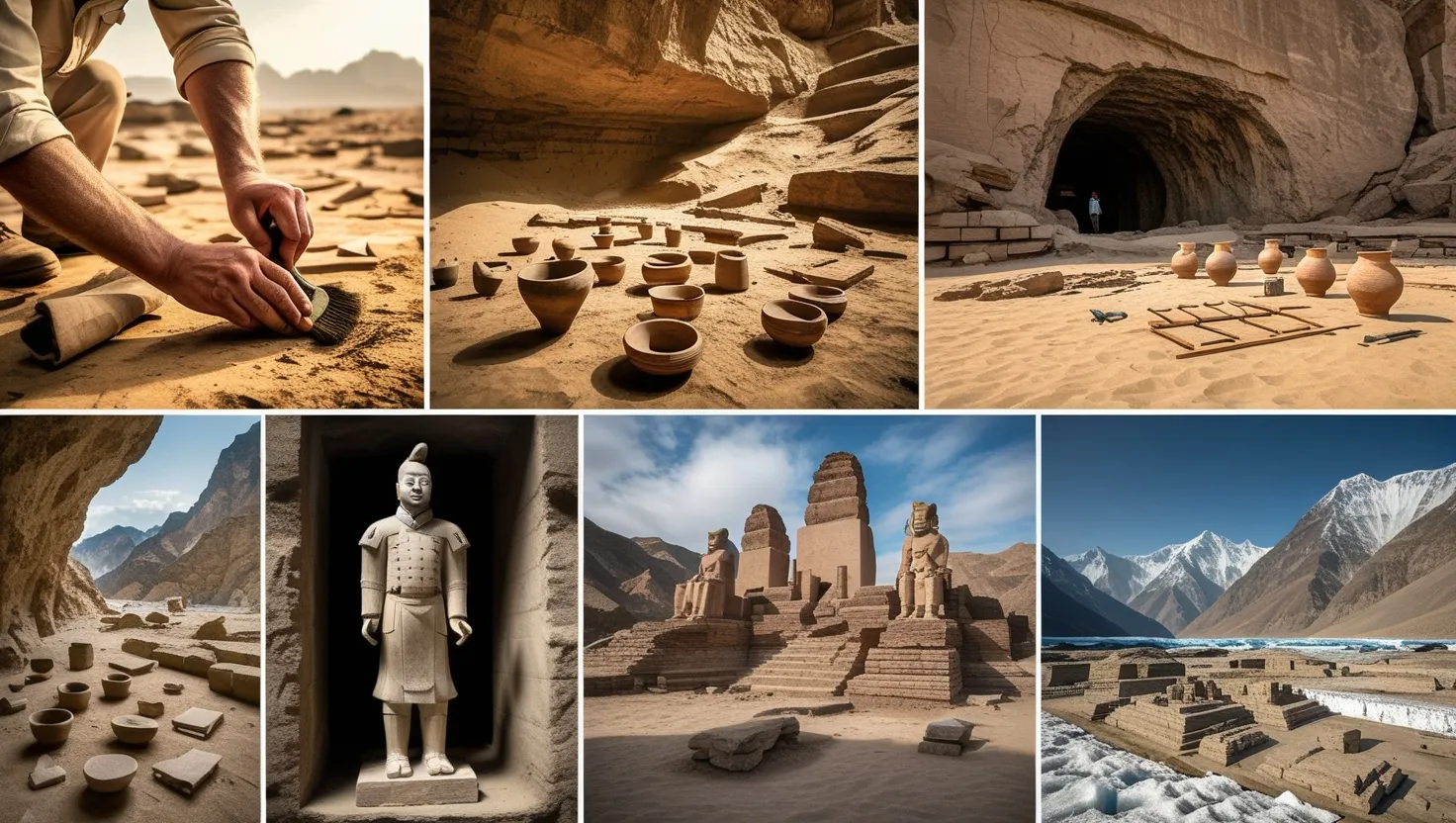

Let’s start in the Chinese countryside in 1974, where a group of farmers set out on an ordinary day to dig a well—nothing romantic, nothing epic. Imagine the surprise when, instead of water, their shovels struck the hardened clay arm of a warrior gazing stoically up through the earth. This was no small artifact. Piece by piece, the world would come to see a silent legion—thousands of Terracotta soldiers, each unique, arranged in tight formations beneath the soil. Until that moment, few could have imagined the scale or ambition of Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of China. His drive for immortality was as literal as it was symbolic, and those warriors were meant to defend him forever in the afterlife. What if the farmers had dug just a few feet away? Would those figures, crafted with astonishing individuality and military precision, have stayed hidden, keeping secret not just the emperor’s paranoia, but his civilization’s technical prowess and artistry?

The magnitude of this find cannot be overstated. There were soldiers of every rank, horses, chariots, and even acrobats and musicians, each assembled with intent. No written record had described such an army; it was a vision lost to time, brought back only by luck. Every time I picture those farmers, boots dusty, pausing in disbelief, I ask myself: How many treasures still slumber beneath us, waiting for the right misplaced spade?

“Chance favors only the prepared mind,” said Louis Pasteur, who was talking about science, but he may as well have been talking about archaeology. The best discoveries, ironically, resist planning. That pattern continued in 1978, though half a world away, in the heart of bustling Mexico City. Urban expansion tends to bulldoze history, but sometimes, history refuses to stay buried. When electrical workers carving a trench for cables shattered a massive stone disk, the resulting commotion drew archaeologists like moths to a flame. The disk depicted Coyolxauhqui, the moon goddess, and revealed the long-lost Templo Mayor—the main temple at Tenochtitlan, hub of the Aztec world.

Think about this: For centuries, Mexico’s capital had grown atop the ruins of its ancient predecessor. The Spanish had razed Tenochtitlan, then built their own city from its stones. Yet layers below, entire temples and ceremonial platforms lingered, silent witnesses to a lost empire. The modern city’s foundation literally rested on the bones of old gods and forgotten kings. The Templo Mayor’s emergence did more than rewrite textbooks; it forced a reckoning with a civilization that had been reduced to myth and rubble. Suddenly, the scale and sophistication of Aztec religious life came sharply into focus. How many of us, scurrying through city streets, realize we may be walking above worlds that shaped everything we know?

Marcus Aurelius once said, “The universe is change; our life is what our thoughts make it.” In this case, the city’s rhythm was interrupted, thoughts were forced to change, and with that, so did the story of Mesoamerica.

Now, picture yourself in the barren, sun-baked hills above the Dead Sea in 1947. A Bedouin boy, searching for a stray goat, lobs a stone into a cave and hears pottery shatter. He crawls inside, expecting treasure or trinkets. Instead, he finds ancient scrolls bundled in jars—texts so old and mysterious their exact contents challenge scholars to this day. The Dead Sea Scrolls, by far the oldest known copies of many biblical texts, became a bridge to worlds both sacred and secular—shedding light on the beliefs and rituals of Judaism at the dawn of Christianity.

What strikes me most is the sheer chance of it all. These manuscripts—some complete, others fragments—had survived through millennia of conflict and neglect, protected not by intention but by desert dryness and darkness. Their words, sometimes echoing verses familiar to millions, sometimes presenting unknown prescriptions and prophecies, force us to see our spiritual origins with new eyes. Who can say how differently we’d understand our shared past without that lost goat and the curiosity it provoked? How many everyday moments pass unnoticed, concealing history’s next revelation?

“It is not down in any map; true places never are,” wrote Herman Melville. The real substance of discovery lies in what cannot be mapped or predicted, in those places that reveal themselves only by accident.

Fast-forward to the windswept plains and hills of western Turkey in the late 1800s. Heinrich Schliemann, a German businessman with a passion for Homer, set out to prove the ancient city of Troy had once existed. Many of his peers called him a dreamer, even a fraud, but his instincts led him to Hisarlik. If you’ve read about Schliemann, you know he was as controversial as he was determined. He blasted trenches through the site, sometimes destroying as much as he revealed. Yet in that reckless, persistent search, he discovered not just one city, but layers upon layers—nine in all—each testimony to centuries of settlement, war, and renewal.

What did this mean for history? For the first time, myth was married to material fact. The stories of Homer, long dismissed as legend, gained weight. Archaeology became something more than treasure hunting; it became the means by which narrative and object could speak to each other.

Here’s a question I often wrestle with: Was Schliemann a pioneer or a vandal? Did his rough methods help or hinder our understanding of ancient Anatolia? While the debate continues, his legacy is clear: Accidents, even chaotic or controversial ones, can upend certainty and force us to ask better questions.

“History is a gallery of pictures in which there are few originals and many copies,” Alexis de Tocqueville wrote. And yet, sometimes, it is the accidental finds—the originals—that set the true shape of that gallery.

Finally, let’s climb high into the Alps, to the border between Austria and Italy, where hikers in 1995 stumbled upon what appeared to be a recent climbing accident. The scene was unsettling: a body, partially exposed from the ice. But the tools and clothing nearby looked strangely ancient. This was Ötzi the Iceman, a man from 3300 BCE, preserved by the glacier’s cold embrace. Ötzi’s examination revolutionized the field of prehistoric studies. His gear, from copper axe to woven grass cape, revealed technologies and diets no textbook had described in such detail.

DNA analysis traced his last meal, the bacteria in his gut, and even clues about his violent death. Forensic techniques transformed him from a scientific curiosity into a flesh-and-blood person. We know about the arrow wound in his shoulder, the flint blade cuts on his hand, the grain residue on his teeth. Imagine gaining such intimate access to a man who lived before the pyramids were built. What can you learn from a single life, frozen by chance, but revived by the eyes of the present?

“I am a part of all that I have met,” wrote Alfred Lord Tennyson. History is not distant or abstract when we touch the body of a man who walked the same earth, spoke unknown words, and met a fate we might recognize in our own times.

So here’s what I want you to ponder: What other twists of fate lie ahead? How much of what we “know” depends on the pitch of a shovel, the leap of a goat, the whim of a worker, or the steps of a mountaineer? We tend to imagine that the past is fixed, but the truth is, every accident is an invitation to question what came before and to look at the present with new humility.

Perhaps the real lesson is this: History is less about chronology and more about curiosity. Every accidental discovery is a mirror—showing us that our past is never truly lost, only waiting to be found, sometimes when we least expect it. If we remain open to surprise, what will we uncover next?