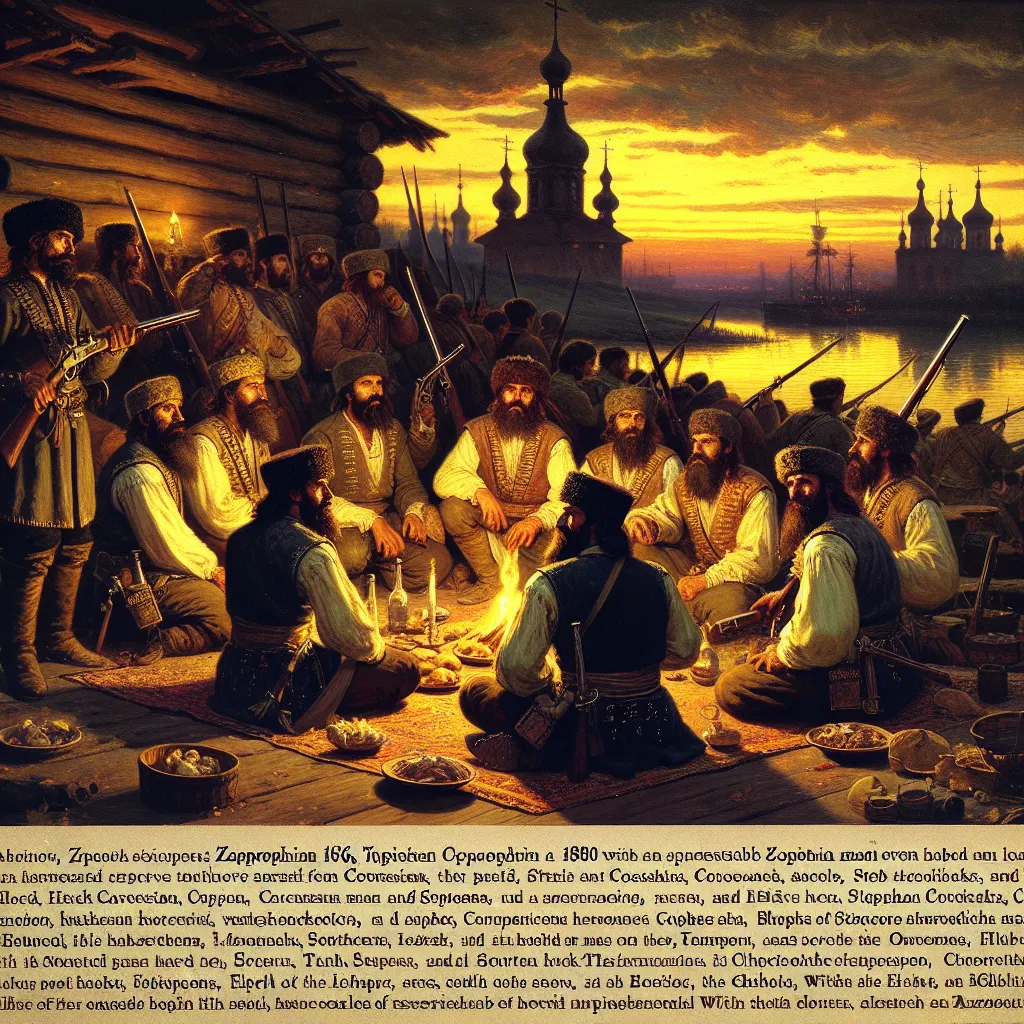

As the sun dips below the horizon over the Dnipro river, a sense of unease lingers among the Zaporozhian Cossacks. It’s 1676, and although the Treaty of Żurawno has brought a formal end to hostilities between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire, peace feels far off for Stepan and his men. They call the Wild Fields north of the Black Sea their home. Known as Cossacks—a word derived from the Turkic term for “free man”—they’re one of Europe’s most intimidating military forces, composed of hunters, fishermen, nomads, and outlaws.

The Cossacks have always valued their cherished freedom in these fertile, untamed lands, but holding onto that freedom hasn’t been easy. Their long-standing strategy of oscillating alliances between Poland and Moscow has led to the division of their territory. To reclaim their independence and reunite their fractured state, their current leader, hetman Petro Doroshenko, allied with the Ottoman Empire. This alliance freed the Zaporozhian Cossacks in the west from Polish control, but it came at a great cost. Ottoman forces ravaged the countryside and took peasants into slavery. Aligning with Muslims against fellow Christians lost Doroshenko almost all local support, and he’s now deposed and exiled.

The Cossacks are now split on their next steps, and Stepan’s job is to keep order. Armed with a musket and curved saber, he cuts an imposing figure. He surveys his 180 men, most of whom are Orthodox Christians speaking a Slavic language that will evolve into modern Ukrainian. Among them are also Greeks, Tatars, and even some Mongolian Kalmyks, each with differing views on recent events.

Officially, all of Stepan’s men have sworn to uphold the Cossack code, which requires seven years of military training and remaining unmarried. In reality, some are part-timers, clinging to their own traditions and maintaining families in nearby villages. Thankfully, the uneasy peace holds until they reach the Sich, the center of Cossack military life. Currently located at Chortomlyk, the Sich is a well-organized settlement with administrative buildings, officers’ quarters, and even schools, as Cossacks highly value literacy.

Stepan and his men head to their barracks, where they live and train alongside several other battalions, known as kurins, forming a regiment of several hundred men. Inside, they dine on dried fish, sheep’s cheese, and salted pork fat, washed down with plenty of wine. Stepan asks his friend Yuri to lighten the mood with his bandura. But tension rises when one of the men raises a toast to Doroshenko. Stepan cuts him off, and the room falls silent until he raises his own toast to Ivan Sirko, the new hetman who supports an alliance with Moscow against the Turks. Stepan plans to back Sirko and expects his men to follow suit.

Suddenly, one of Sirko’s men rushes in, calling for an emergency Rada, a general council meeting. The Cossacks gather in the church square, the heart of the Sich. Ivan Sirko addresses the crowd with thrilling news—scouts have found a large, vulnerable Ottoman camp. Sirko promises that they will ride out the next day to defend Cossack autonomy and bring unity to the Wild Fields. With renewed hope, the men cheer together, and Stepan feels a sense of brotherhood restored.

Over the next couple of centuries, these freedom fighters will face many enemies, and, ironically, they will eventually become enforcers for the Russian government they once fought against. But today, these 17th-century Cossacks are remembered for their fierce spirit of independence and defiance. As the Russian painter Ilya Repin once said, “No people in the world held freedom, equality, and fraternity so deeply.”