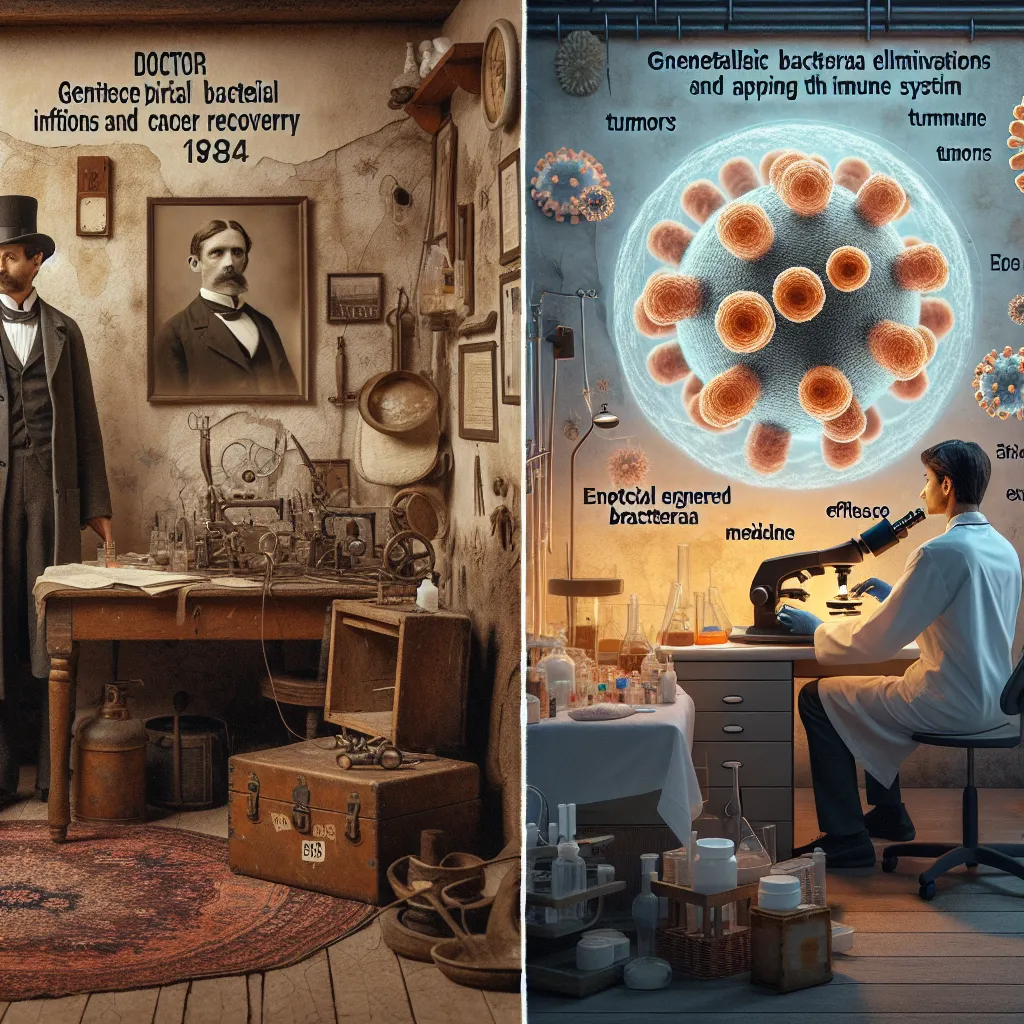

In 1884, a man’s situation went from bad to worse when he was diagnosed with a rapidly growing neck cancer and then developed a skin infection. But, an unexpected twist occurred: as he recovered from the infection, his cancer also began to disappear. When Doctor William Coley checked on him seven years later, the cancer was gone. Coley believed the bacterial infection had somehow triggered the patient’s immune system to attack the cancer.

Coley’s lucky discovery led him to pioneer the deliberate injection of bacteria to treat cancer. Fast forward more than a century, and scientists now have an even smarter approach: they’ve found ways to program bacteria to deliver drugs right to tumors.

Cancer happens when cells malfunction and multiply uncontrollably, forming tumors. Treatments like radiation and chemotherapy aim to kill these cancerous cells but often harm healthy tissues too. Some bacteria, like E. coli, have the ability to grow inside tumors specifically. Tumors provide a safe environment for these bacteria to multiply, hidden from the immune system. Instead of causing infections, these bacteria can be re-engineered to carry cancer-fighting drugs, acting like undercover agents.

The field of Synthetic Biology focuses on programming bacteria to perform new tasks. Scientists can tweak bacterial DNA to make them produce molecules that fight cancer. They create biological circuits to make bacteria behave in specific ways, depending on various factors like low oxygen and pH levels in tumors.

One clever type of biological circuit, called a synchronized lysis circuit (SLC), lets bacteria deliver medicine on a set schedule. Inside the tumor, bacteria grow and start making anti-cancer drugs. When they reach a critical number, a kill-switch makes them burst, releasing the drugs and killing some bacteria to control the population. Some bacteria survive to keep the cycle going, ensuring a steady release of medication.

This method has shown promise in mouse trials. Scientists managed to eliminate lymphoma tumors by injecting bacteria. The added bonus? The bacteria also primed the immune system to recognize and attack untreated tumors elsewhere in the mouse’s body.

Unlike some treatments that target specific cancers, bacteria are programmed to identify characteristics common to all solid tumors. They hold potential to become high-tech sensors that could one day prevent and treat diseases even before symptoms appear.

While high-tech nanobots are promising, bacteria—shaped by billions of years of evolution—may offer a natural starting point. With advances in synthetic biology, the future of medicine could get really exciting.