Language is a vital part of our lives, even though we often overlook its significance. It allows us to chat with friends, dive into novels, send messages, and express our thoughts and emotions. It’s difficult to envision not being able to articulate our thoughts into words. But that’s precisely what happens if the brain’s intricate language networks are disrupted by a stroke, illness, or trauma. This condition, known as aphasia, impacts all aspects of communication.

People with aphasia don’t lose their intelligence. They know what they want to say but struggle to express it. They may mix up words, like saying “dog” instead of “cat” or “house” instead of “horse.” Sometimes, their speech may not make sense at all. Aphasia is divided into two main categories: fluent (receptive) and non-fluent (expressive). Those with fluent aphasia might speak with normal vocal inflection but their words may lack meaning. They also have trouble understanding others and might not realize their speech errors. On the other hand, individuals with non-fluent aphasia may understand speech well but face long pauses and grammatical mistakes while speaking.

We’ve all experienced moments when a word is on the tip of our tongue, but aphasia makes it hard to name even simple, everyday objects. Reading and writing also become daunting tasks. So, how does this language breakdown happen?

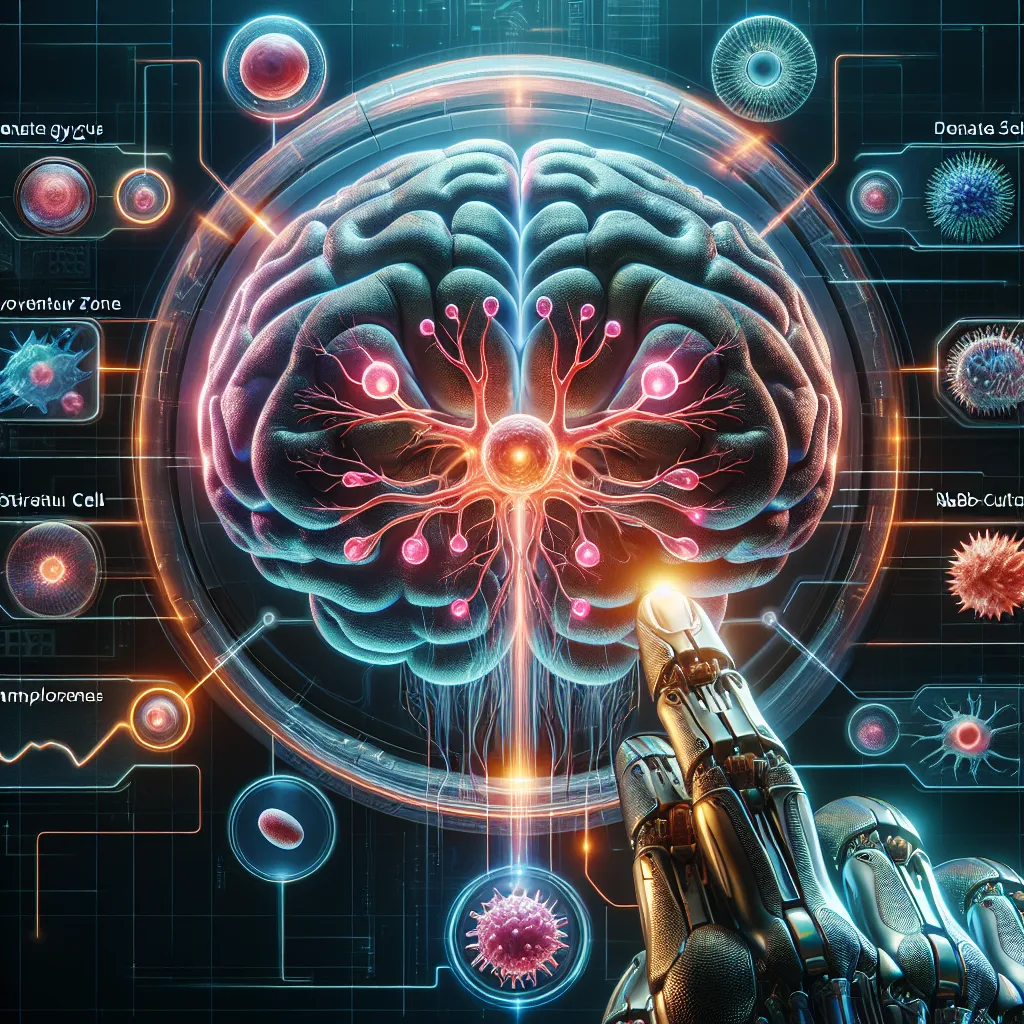

The human brain has two hemispheres, with the left one mainly responsible for language. This was first discovered in 1861 by Paul Broca, a physician who studied a patient that could only say “tan.” After the patient passed away, Broca found a large lesion in the left hemisphere, now called Broca’s area. This region helps in naming objects and coordinating speech muscles. Just behind it is Wernicke’s area, near the auditory cortex, which gives meaning to speech sounds. Damage to these areas can lead to aphasia.

Thankfully, other brain areas support these language centers and aid in communication. Even parts of the brain that control movement are linked to language. When we hear words like “run” or “dance,” the brain areas responsible for movement activate as if we were actually running or dancing. The right hemisphere also helps with language, enhancing the rhythm and tone of our speech. These non-language brain areas play a role in aiding communication for people with aphasia.

Aphasia is more common than many think. In the U.S. alone, about a million people have it, with around 80,000 new cases each year. It affects about one-third of stroke survivors, making it more prevalent than Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis, yet it remains less known. A rare form of aphasia, known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA), isn’t caused by stroke or injury but by a type of dementia where language loss is the first symptom. The aim in PPA treatment is to maintain language function as long as possible before other dementia symptoms appear.

For aphasia caused by stroke or trauma, speech therapy can help improve language skills. The brain’s ability to heal, known as brain plasticity, allows surrounding areas to take over some functions during recovery. Researchers are experimenting with new technologies to promote brain plasticity in people with aphasia.

Many individuals with aphasia feel isolated, fearing others won’t understand them or give them enough time to speak. By being patient and flexible, we can help them overcome the barriers of aphasia and open the door to communication once more.