Taoism is a rich and multifaceted tradition, deeply ingrained in China’s religious tapestry. Despite its significance, many only know about the early Taoist sages like Lao Tzu and the Dao De Jing. The common narrative glorifies this classical period, yet overlooks the extensive developments in later Taoist traditions.

We often hear Taoism divided into philosophical and religious branches. This split, however, is misleading, as it stems from colonial and orientalist views that see philosophical Taoism as the “pure” form. Scholars now criticize this division, recognizing it as an oversimplification that misrepresents Taoism’s true essence.

Yet, it’s undeniable that Taoism evolved from loosely organized practices in its early days to more structured forms during the Han Dynasty. The first organized Taoist movement, Tianshi Dao or the Way of the Celestial Masters, was established by Zhang Daoling after receiving a revelation from the deified Lao Tzu. This movement formed a cornerstone for future Taoist developments.

As centuries passed, new Taoist sects and practices emerged. The Celestial Masters were followed by movements like Taiqing, Shangqing, and Lingbao, each bringing new beliefs and rituals. These later forms of Taoism introduced ideas about death, the afterlife, and even immortalization.

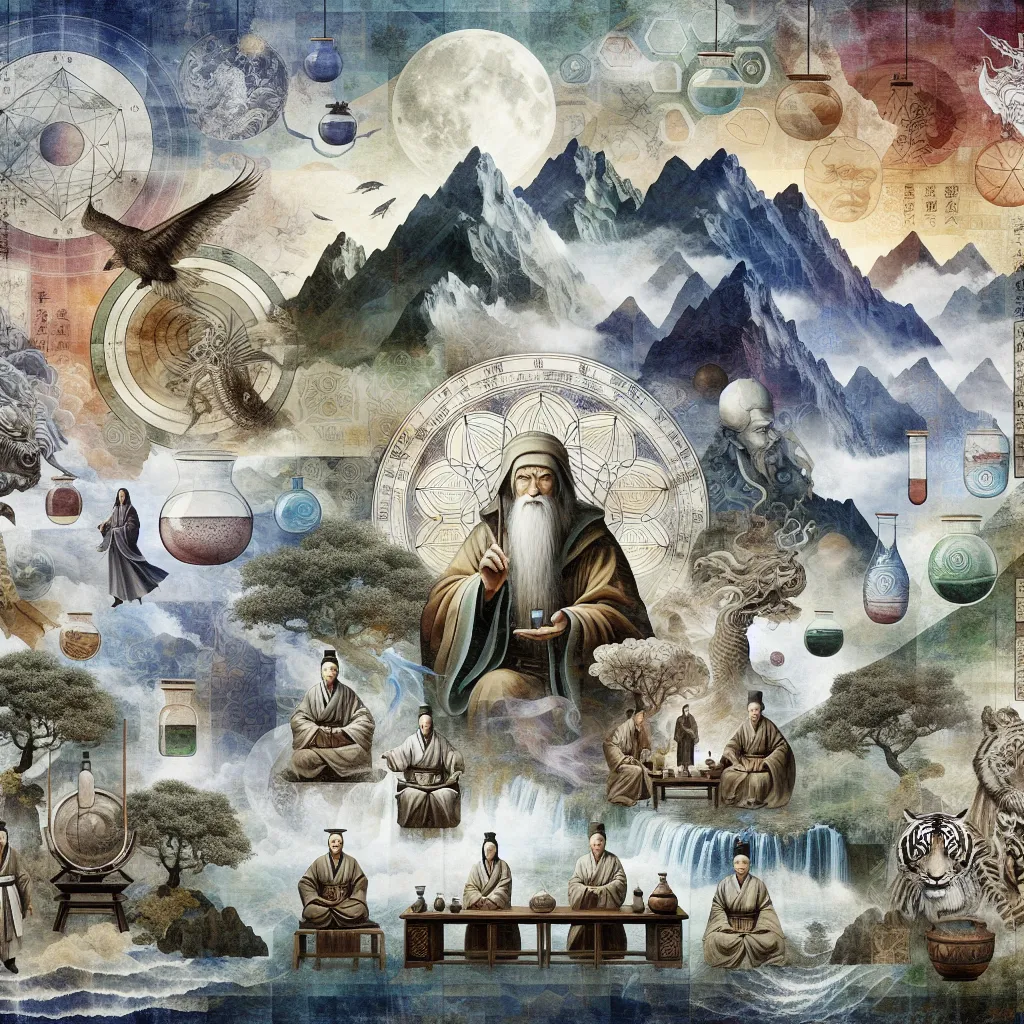

Classical Taoism emphasized practices like apophatic meditation, where practitioners sought oneness with the Dao. However, later periods explored the concept of immortality, not as a mere mystical union with the Dao, but as a tangible goal. This led to the rise of Taoist alchemy—both external, involving the concoction of elixirs, and internal, focusing on spiritual transformation.

Internal alchemy or Neidan became especially prominent, aiming for immortality through the cultivation of three treasures: Jing (vital essence), Qi (vital breath), and Shen (spirit). Practitioners sought to transform Jing into Qi, Qi into Shen, and finally merge Shen with the void, achieving a state of oneness with the Dao.

These practices were esoteric, often taught by a master and shrouded in symbolic, poetic language. For instance, texts might describe meditative practices using imagery of dragons and tigers, wisely keeping the teachings hidden from the uninitiated.

The techniques involved meditation, visualization, dietary restrictions, and asceticism, with vital energy circulated through the body to integrate different aspects of the self. This spiritual process was described metaphorically, likening the growth of an immortal embryo within the practitioner.

Throughout its history, Taoism has absorbed influences from other religions, especially Buddhism. This cross-pollination led to further development of Taoist monasticism and practices. By the Song and Ming Dynasties, Neidan had solidified its place alongside other Taoist rituals.

Understanding Taoism means appreciating both its early texts and its later traditions. Scholars now embrace a more nuanced view, dispelling the misconception that Taoist evolution diluted its essence. Instead, the tradition’s depth lies in its ability to adapt and incorporate new ideas while staying true to its core beliefs.

Exploring Taoism reveals a complex and colorful tradition, much deeper than typically portrayed. There’s more to discover about its practices, beliefs, and historical evolution—far beyond the Dao De Jing. Let’s continue this journey, unraveling the mysteries and beauty of Taoism together.