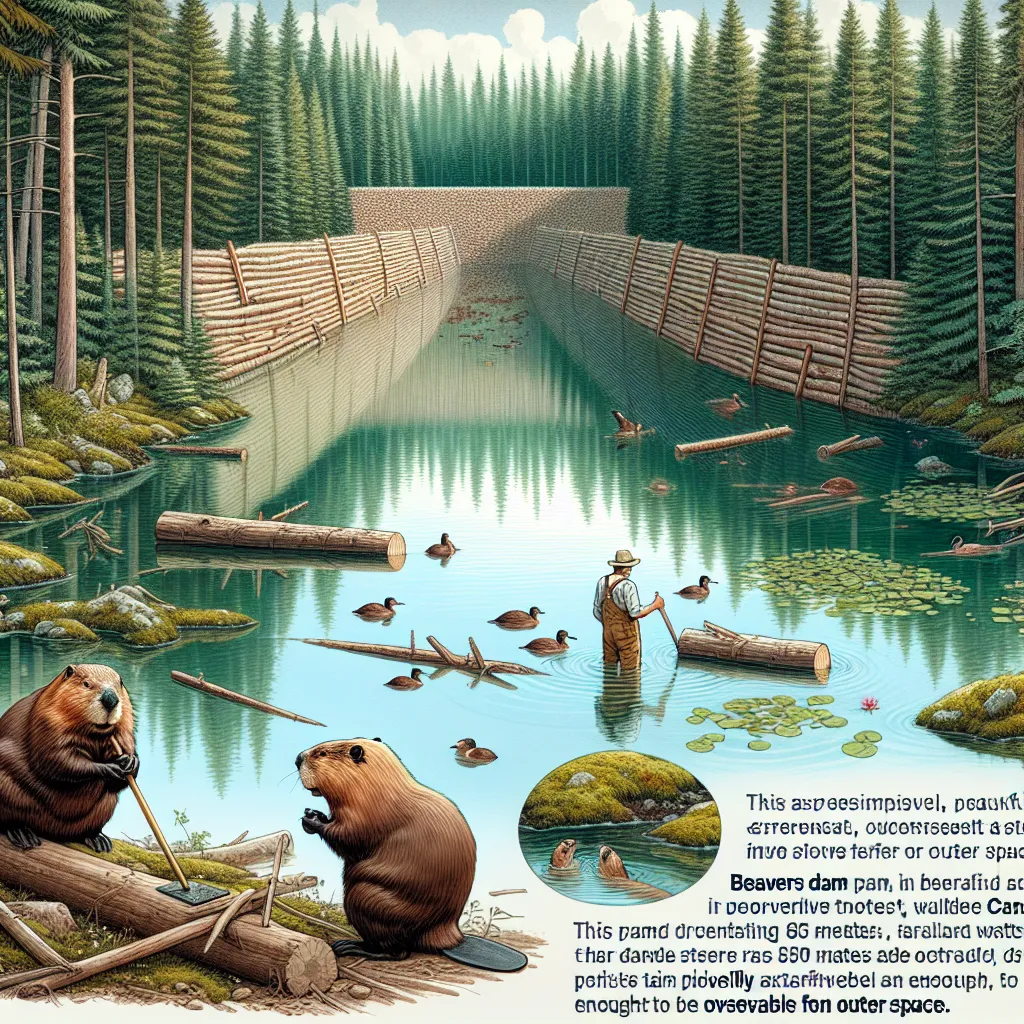

In the secluded woods of northern Canada lies the world’s longest beaver dam, a colossal 850-meter-long structure so grand it is visible from space. This enormous dam, maintained by generations of industrious beavers, has transformed the landscape, creating a pond that holds an astonishing 70 million liters of water—a perfect habitat for its busy engineers. But even smaller beaver dams have significant environmental effects.

How do beavers reshape their surroundings and build such formidable structures? Consider this example of a beaver in the northwestern United States. Standing just under 2 feet tall, this determined little architect belongs to the world’s second-largest rodent species. On land, he’s vulnerable to predators, but once he constructs a lodge surrounded by water, he’s much safer.

Beavers don’t build dams just anywhere. They follow the sound of running water to find the perfect spot—a medium-sized stream with a soft, muddy bottom. Avoiding rocky sites, our beaver combines vegetation, mud, and sticks to start a small bank along the stream’s edge. With an impressively strong bite, he chews logs into sturdy sticks, which he rolls into the water and secures into the soft streambed.

There are different styles of beaver dams, but our beaver chooses a concave shape to dissipate the force of the flowing water. He adds large rocks to reinforce areas where the water flows strongest. Depending on the stream’s speed, the dam’s length, and the number of beavers working, these industrious creatures can build remarkably fast. In some cases, they have been known to rebuild dams overnight after humans have removed them, sometimes making them even larger.

Most beaver dams, like our beaver’s project, are just a couple of meters long. Working alone, it might take several days to complete. Once the dam spans the stream, water begins to back up, creating a pond. As the pond grows, the beaver extends the dam to block water flow around the sides, allowing some water to leak downstream to reduce pressure and regulate pond levels.

A larger pond means a bigger territory for the beaver. Since beavers can hold their breath for up to 15 minutes, they can easily access food along the shorelines. During the fall, our beaver stockpiles an impressive amount of food for winter, and he hopes to find a mate to share it with. Beavers are territorial but bond for life. When the pond freezes, the beaver couple splits their time between fetching food from their cache and starting a family.

By summertime, juveniles help with dam maintenance, food gathering, and taking care of younger siblings. After 2 to 3 years, these young beavers will leave to find their own territories and mates, but the ancestral dam can last for decades. Descendants or new beavers moving in will continue to uphold the dam.

Beaver dams are common, with some regions hosting up to 40 dams per kilometer of stream. These structures benefit surrounding wildlife, providing nesting sites and refuges for various waterfowl. Beaver channels connect water bodies, enhancing the biodiversity between water and land.

Humans too, benefit from these natural engineers. Beaver ponds help replenish groundwater stores by creating large surface water expanses and, like manmade dams, they slow floodwaters. By simply following their instincts, beavers significantly impact the ecosystem downstream, proving they are truly remarkable architects of their environment.